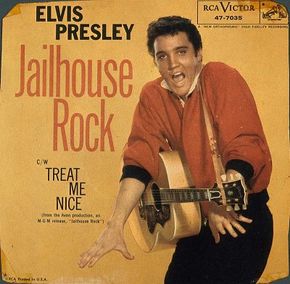

Elvis Presley and Jailhouse Rock

The next movie-and-album release from Elvis Presley was Jailhouse Rock. The extended-play (EP) album released as the soundtrack for Jailhouse Rock serves as a snapshot of the times. EP albums were a fixture in the recording industry during the 1950s, tapering off in popularity during the 1960s. Generally containing four to five songs, an EP offered the listener something more than a single, but it cost less than a long-playing album, which averaged ten to twelve songs.

Elvis' final commercially released EP was the soundtrack for Easy Come, Easy Go in 1967. The Jailhouse Rock EP also indicated the enormity of Elvis' popularity in the winter of 1957-1958, charting for an astounding 49 weeks and remaining at No. 1 for 28 weeks. Billboard named it EP of the Year for 1958. The highlight of the EP was the famous title song -- the embodiment of the Presley persona during that era.

Advertisement

Penned by the legendary Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, "Jailhouse Rock" became another No. 1 record for Elvis. It entered the British charts at No. 1, making it the first single ever to do so. The rock 'n' roll songwriting duo was commissioned to write most of the songs for the movie Jailhouse Rock, though they were less than enthusiastic about the assignment.

Prior to "Jailhouse Rock," Elvis had recorded a handful of songs from Leiber and Stoller, including "Hound Dog," "Love Me," and a couple of tunes from Loving You. The two songwriters were not impressed with Elvis' interpretation of their material. Leiber and Stoller had a tendency to write hard-driving, R&B-flavored tunes with satiric or tongue-in-cheek lyrics that could be understood at more than one level.

Elvis, on the other hand, performed most of his material straight, as when he recorded the duo's "Love Me," which they had originally intended as a lampoon of country-western music. Leiber and Stoller also felt that Elvis' foray into R&B territory was a fluke, and they were suspicious of his interest in blues and rhythm-and-blues.

When the three met during the April 1957 recording session for "Jailhouse Rock," Leiber and Stoller quickly changed their minds about Elvis. They realized he knew his music and he was a workhorse in the studio. The pair took over the recording sessions, serving as unofficial producers of "Jailhouse Rock," "Treat Me Nice," "(You're So Square) Baby, I Don't Care," and other tunes. Their collaboration with Elvis and his musicians on "Jailhouse Rock" resulted in the singer's hardest-rocking movie song. D.J. Fontana said of his drum playing, "I tried to think of someone on a chain gang smashing rocks."

The short period of time that Leiber and Stoller worked with Elvis proved beneficial to both sides. The irony and ambiguity in the lyrics of "Jailhouse Rock" gave Elvis one of his most clever rockers, while the singer's sincere and energetic delivery prevented the song from becoming too much of a burlesque -- a tendency with some of the Leiber and Stoller songs written for the Coasters. These songwriters hung with Elvis long enough to contribute to the King Creole soundtrack, among other projects, but eventually they ran afoul of Elvis' management for trying to introduce him to new challenges.

With its combination of hard-rocking tunes and romantic ballads, the Jailhouse Rock EP ably supported the film of the same title. King Creole boasts a powerful cast and a skilled director, and Blue Hawaii features slick production values, but the gritty, low-budget Jailhouse Rock remains Elvis Presley's best film. If Elvis the rock 'n' roll rebel liberated a generation from the values, tastes, and ideals of their parents, then Jailhouse Rock is the only Presley film that speaks directly to the feral, sensual, and unruly nature of rock 'n' roll music.

Elvis' musicals belong to that genre known as the "teenpic" or the teen musical, in which rock 'n' roll performers were showcased in musical vehicles designed to cash in on the immense popularity of youth-oriented music. From Rock Around the Clock, featuring real-life rocker Bill Haley, to Rock, Pretty Baby, starring actors pantomiming to ersatz rock tunes, producers and studios pandered to the teenage audience by combining teen fashion, teen jargon, and teen idols with a healthy dose of generational conflict.

Released in 1957, Jailhouse Rock offers more than a superficial rundown of the latest fads and fashions, however, and it excludes the standard clash between generations. The plot features an insider's look at the rock 'n' roll record business (as interpreted by Hollywood) through the character of Peggy Van Alden, a record exploitation "man" (1950s title for a record promoter) who helps ex-con Vince Everett (Elvis' character) launch a singing career.

Because the audience sees the business through Peggy's point of view, the film's treatment of rock music differs from other teenpics. For example, rock 'n' roll is an established, accepted style of music when the story begins, and there is no organized resistance to it by authority figures. In general, the attitude toward the music in the script is both knowing and respectful, serving to validate rock 'n' roll as a popular art form -- an important consideration to teenagers of the era.

One scene does acknowledge the conflict in musical tastes between the generations. Vince and Peggy drop in on a cocktail party hosted by Peggy's parents. Mr. Van Alden is a college professor, so his friends and associates are depicted as upper-middle-class professionals. Bored and out of place, Vince is standing beside a group talking about music. A woman exclaims, "Some day they'll make the cycle back to pure old Dixieland. I say atonality is just a passing phase in jazz music. What do you think, Mr. Everett?" Vince snarls, "Lady, I don't know what the hell you're talking about!"

The scene curtly draws a line between the two types of music by generation and by class, and it concludes without the two sides attempting to reconcile, which was unusual for teenpics of this era. Instead, the jazz fans come off as snobbish and dull, while Vince's ultimate success with records, television, and movies validates his style of music. For once, rock 'n' roll bests another type of music and its proponents without a character having to explain or defend rock 'n' roll's existence.

The heart of Jailhouse Rock is the character of Vince Everett, who swaggers and prowls through the film with attitude and magnetism. Despite his Hollywood-style conversion in the final moments, it is Vince's impudence and haughty defiance that stay with the viewer long after the final fadeout. The character embodies the rebellious spirit and sexuality of rock 'n' roll, in much the same way that Elvis did in his career. This close identification between real-life performer and fictional character is the film's strength.

Several scenes and shots illustrate the similarities between the performing styles of Elvis and Vince and help audiences make the connection. Of particular interest is a scene in which Vince spends time in a recording studio searching for a singing style. Listening to himself croon "Don't Leave Me Now," he realizes that he lacks a personal style.

After rocking the tune just a bit, Vince discovers how "to make the song fit him." The scene echoes Elvis' efforts to work through a personal style at Sun Records back in the summer of 1954, an often repeated tale in Elvis' publicity. To make the connection between Vince and Elvis even stronger, the musicians used in the scene were Elvis' own backup band.

Also, Vince's costume in this scene duplicates Elvis' unique style of clothing. With his baggy black pants held in place by a thin belt and his tight-fitting shirt with turned-up collar and rolled-up sleeves, Vince sports the type of ultrahip attire Elvis purchased at Lansky's clothing store on Beale Street in Memphis. Similarly, Vince's hairstyle is a slightly cleaned-up version of Elvis' notorious ducktail and sideburns. Costuming and hairstyle might seem like minor details now, but to fans and audiences of the era, the similarities would have been obvious and meaningful.

Most of the songs were written especially for the film by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, with Stoller making a brief appearance as a studio pianist during the scene in which Vince records "Don't Leave Me Now." The participation of these famous rock 'n' roll scribes in the making of the film adds an authenticity to it, as does the elaborate choreography for the title tune. Elvis participated in choreographing "Jailhouse Rock," with the steps based on his controversial performing style.

Thus, Elvis' image defined the role of Vince Everett as much as Vince perpetuated Elvis' image as a rebellious rock 'n' roller. For MGM and the producers, this guaranteed a sizable audience of Elvis fans. For audiences of the era, it added credibility and authenticity to the film. For contemporary audiences, it captured Elvis in his most popular incarnation -- the young rebel who not only changed the course of popular music but also gave a generation an identity and an attitude.

In retrospect, Jailhouse Rock may be Elvis' best film because of the way it captures the rebellious rock 'n' roll attitude of the 1950s. Yet, Elvis appeared in three other films between 1956 and 1958, and each of them spawned hit singles and chart-topping albums.

Despite the obvious attempt to cash in on Elvis' popularity as a recording phenomenon, Love Me Tender, Loving You, Jailhouse Rock, and King Creole are decidedly different from those films associated with Elvis during the 1960s. Musical dramas with solid supporting casts, the 1950s films benefited from the contributions of veteran Hollywood producers and directors. Chief among them was Hal Wallis.

For his next movie, King Creole, Elvis again expanded his acting talents, working with an incredibly talented supporting cast. See the next section to learn more about Elvis Presley and King Creole.