Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show

Two weeks after Elvis' first RCA recording session, he made his first television appearance on Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey's weekly Stage Show. During the next eight weeks, he appeared on this variety series five more times, and each time the show received better ratings. The first show, however, was only moderately successful and was beaten in the ratings by The Perry Como Show.

Stage Show was typical of television variety programs in the mid-1950s. Understanding the nature of these variety shows helps us to understand why Elvis created such a stir. With an hour-long format, Stage Show featured performances by a diverse group of entertainers, ranging from popular singers to animal acts to ballet dancers. Each week a guest host introduced some of the acts for that particular program.

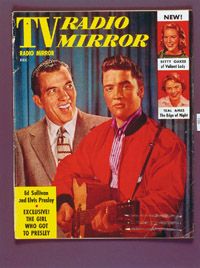

Advertisement

On Elvis' first appearance, he was introduced by Cleveland disc jockey Bill Randle, who was supposedly the first radio personality to play an Elvis record outside the South. Randle, however, would be the only person featured on any of Elvis' Stage Show appearances who had any connection with the young singer.

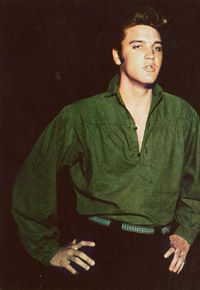

The other hosts and guest stars who appeared with Elvis included jazz singers Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald, stand-up comedians Joe E. Lewis and Henny Youngman, a chimpanzee act, an acrobatic team, and an 11-year-old organist. Compared to these types of entertainers -- who were considered suitable for family audiences -- Elvis' new, high-powered music and dynamic performing style seemed alien. The young singer's Beale Street clothing and ducktail haircut made him stand out even more.

On his first appearance, Elvis was visibly nervous. He sang "Shake, Rattle, and Roll" and "Heartbreak Hotel," doing a little shaking and shimmying, and then quickly moved offstage. By his final appearance, more of an interaction between Elvis and his audience took place as the young man worked hard to drive the girls in the crowd into a screaming frenzy.

When he strummed the opening chord of "Heartbreak Hotel" on his guitar, a burst of screams and applause broke out. Elvis hesitated for a moment, tantalizing the audience with anticipation. As he broke into song, he moved across the stage, shaking his shoulders and swinging his legs.

Certain moves were obviously designed to elicit emotional responses from the girls, and Elvis' smiles proved he was delighted at this explosive effect on his female fans. The interaction between Elvis and his fans was much like a game: He teased the women with his provocative moves; they screamed for more; he promised to go further; sometimes he did.

In late spring of 1956, Elvis appeared on The Milton Berle Show for the first time. The show was broadcast from the USS Hancock, which was docked at the San Diego Naval Station. Despite the novel location, this television appearance is barely mentioned in biographies or other accounts of Elvis' career, because his second appearance on the Berle program has completely overshadowed it.

This appearance on June 5 fanned the flames of the nationwide controversy over his hip-swiveling performing style. Elvis sang "Hound Dog" for the first time on television that spring night. When he began the song, no one knew what to expect, because the tune was new. But the audience responded immediately with enthusiasm. Elvis then went a bit further in his performance: He slowed down the final chorus of the song to a blues tempo, and he thrust his pelvis to the beat of the music in a particularly suggestive manner. The studio audience went wild with excitement.

The next day, the press nicknamed him "Elvis the Pelvis." Many described his act by comparing it to a striptease. Jack Gould of The New York Times declared, "Mr. Presley has no discernible singing ability," while John Crosby of the New York Herald Tribune called Elvis "unspeakably untalented and vulgar." The criticism prompted parents, religious groups from the North and South, and the Parent-Teacher Association to condemn Elvis and rock 'n' roll music by associating both with juvenile delinquency.

Elvis could not understand what all the fuss was about: "It's only music. In a lot of papers, they say that rock 'n' roll is a big influence on juvenile delinquency. I don't think that it is. I don't see how music has anything to do with it at all....I've been blamed for just about everything wrong in this country."

After The Milton Berle Show, Colonel Parker booked Elvis on The Steve Allen Show, a new variety program that aired at the same time as Ed Sullivan's immensely popular show. Allen hated rock 'n' roll, but he was aware of the high ratings Berle's show received when Elvis appeared. He was also aware of the controversy.

To tone down Elvis' sexy performance, Allen insisted that he wear a tuxedo during his segment, and he introduced him as "the new Elvis Presley." Elvis sang one of his latest singles, a slow but hard-driving ballad called "I Want You, I Need You, I Love You."

Immediately after that number, the curtain opened to reveal a cuddly basset hound sitting on top of a tall wooden stool. Elvis sang "Hound Dog" to the docile creature, which upstaged the singer with his sad-eyed expressions. Allen used humor to cool down Elvis' sensual performing style, prohibiting him from moving around much on stage and even preventing him from wearing his trademark Beale Street clothes. The fans were furious, and they picketed NBC-TV studios the next morning with placards that read, "We want the gyratin' Elvis."

Later in the program, Elvis joined Allen, Imogene Coca, and fellow Southerner Andy Griffith in a comedy sketch that satirized country-western programs, not unlike Louisiana Hayride. Many of the jokes were condescending toward Southern culture. Allen's presentation of Elvis singing to a dog plus the appearance of the "hayseed" sketch actually ridiculed Elvis. Steve Allen was the real winner that night, because his show beat Sullivan in the ratings.

Elvis had established himself as an entertainer who could attract a large television audience and boost ratings, so it's not surprising that after many rejections, the Colonel finally arranged for Elvis to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, a highly rated, prime-time variety program.

Sullivan, who was a powerful figure in the industry, had stated publicly that he would not allow Elvis to appear on his show because it was a family program. But ratings speak louder than scruples, and Sullivan backed down from this stance after The Steve Allen Show was so successful. Elvis was paid an unprecedented fee of $50,000 for three appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. This was a lot more than the $5,000 per show Colonel Parker had asked for only a few weeks earlier when Sullivan turned him down.

Elvis' performance on The Ed Sullivan Show is cemented in the annals of rock music history because of the censors' decision to shoot the volatile young singer only from the waist up. However, contrary to popular belief, this decision was not made until his third appearance.

Actor Charles Laughton served as substitute host the night of Elvis' first appearance because Sullivan was recuperating from an auto accident. In kinescopes and video footage of that performance, Elvis can be seen in full figure, crooning "Love Me Tender" and "Don't Be Cruel," then later belting out "Hound Dog" and "Ready Teddy."

Elvis' third and final appearance on Sullivan's show on January 6, 1957, contains the legendary moments when the CBS censors would not allow his entire body to be shown. Seen only from the waist up, Elvis still put on an exciting show, singing seven songs in three segments. In one segment, Elvis and the Jordanaires sang "Peace in the Valley," which Elvis dedicated to the earthquake victims of Eastern Europe.

But it was his rendition of such Presley hits as "Heartbreak Hotel" and "Hound Dog" that stirred up the studio audience. Their screams and applause clued the television viewers in to what Elvis was doing out of camera range, almost subverting the censors' intent. Once again, the interaction between Elvis and the studio audience added to the power of his performance. After Elvis' final number, Sullivan declared him to be "a real decent, fine boy" -- a rather hypocritical statement considering what he and the censors had just done to Elvis' act.

For years people have wondered why Elvis was censored during his third appearance on Sullivan's show. The simplest and most probable explanation is that Sullivan received negative criticism about Elvis' earlier appearances. Other, more outrageous explanations include the theory that the Colonel forced Sullivan to apologize publicly for remarks he'd made about Elvis to the press the previous summer, and the waist-up-only order was Sullivan's way of getting back at Parker.

The wildest explanation was offered by a former director of The Ed Sullivan Show, who said that during his second appearance, Elvis put a cardboard tube down the front of his trousers and manipulated it to make the studio audience scream. To avoid a repeated occurrence of that behavior, Sullivan supposedly insisted on the above-the-waist coverage for Elvis' final appearance. None of these explanations offers any real insight into Sullivan's motivations but all add to the folklore surrounding this event, thereby enhancing Elvis' image as a notorious rock 'n' roller.

Elvis' image also owed a lot to his portrayal in the media. See the next section to learn more about Elvis and the press.