The Boston Braves had long been one of the worst organizations in baseball. Shortly after the "Miracle Braves" of 1914 went from last place on July 4 to a pennant and a World Series sweep of Connie Mack's defending champion Athletics, the club had begun a yearly ritual of spending its summers in the second division.

Between the years of 1922 and 1932, the Braves had never finished above fifth place or posted a winning record, and their overall winning percentage for the 1920s was .394. The Red Sox (.370) were one of only two clubs to do worse, lending even more credence to the theory that the sale of Babe Ruth had thrown a curse over Boston baseball. Nevertheless, Babe Ruth suddenly seemed destined to become a Boston Brave.

More Braves Misery

Yearly attendance at Braves games had fallen as low as 117,478 (the same number as a good week at Yankee Stadium), and even after the fortunes of the club began rising under the guidance of manager Bill McKechnie, the crowds were slow in catching on.

A brief run at the pennant and an eventual fourth-place finish had attracted a record 517,803 in 1933, but another fourth place showing and the club's best record since 1916 (83-71) drew just 303,205 to cold and cavernous Braves Field the following summer. Part of the trouble was lousy weather, but a more dangerous reason was just a few trolley stops down the road.

Manager Tom Yawkey was spending freely in acquiring the likes of A's pitching great Lefty Grove, the Ferrell brothers (pitcher Wes and catcher Rick), and now Joe Cronin to upgrade the Red Sox, and he had refurbished cozy Fenway Park into one of the nicest places to watch baseball in the country.

The Braves had only one legitimate star in slugger Wally Berger (who held the National League rookie home run record with 38). Their park was a huge, concrete monument to the dead-ball era with center field fences that at one point stood over 500 feet from home plate. Berger had been the only Braves player to ever hit 20 homers in a season there, and fans increasingly grew to favor the long-ball action at tiny Fenway.

Cool winds that blew into Braves Field off the Charles River and smoke that drifted in from a rail yard behind left field didn't help matters either. And the problems of the park were only compounded by ownership woes.

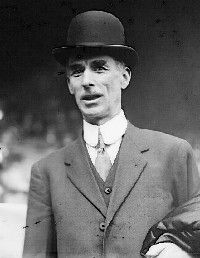

The Braves had somehow made money each year from 1930 through 1933, but team president and co-owner Judge Emil Fuchs had developed an old Ruthian habit of getting rid of it as fast as it came in.

He claimed to have spent $159,000 against a $150,000 profit in 1933 alone pursuing new talent, and he still owed as much as $200,000 to minority partners Charles Adams and Bruce Wetmore -- who had bailed him out of ruin by purchasing substantial amounts of stock back in 1927. He made quite an effort to sell his interest but could find no takers. Just like Red Sox owner Harry Frazee a little over a decade before, the judge was in serious trouble.

Fuchs Hatches a Plan

Shortly before the 1934 National League meetings, Fuchs came up with a plan to bail himself out of debt. Braves Field would be converted into a dog racing facility, and the team would move in with the Red Sox and share Fenway Park.

The two clubs had established a good working relationship two decades before, when the Braves borrowed Fenway for the 1914 World Series (their stadium was being built at the time), then returned the favor by offering up Braves Field and its 40,000 seats for both the 1915 and 1916 Series. Boston teams had won the championship all three times, and everybody appreciated the larger Series shares.

This time things weren't quite so easy. Yawkey was vehemently against the idea -- his goal was to make the Red Sox the only Boston team folks wanted to see -- and Fuchs's fellow NL owners didn't like the thought of a major league baseball field being overrun by gamblers and greyhounds.

The judge eventually gave up his dog dreams. When the owners of Braves Field threatened to evict Fuchs and lease to the Boston Kennel Club, the National League stepped in to guarantee rental on the park and loaned Fuchs $7,500 to meet spring training expenses.

His ownership saved for the moment, the judge soon had another idea. The biggest day in Boston baseball the previous year had been when Babe Ruth came to town, and Boston Mayor James Michael Curley urged the desperate Fuchs to hire the Babe as manager.

The judge refused, saying he was happy with his current arrangement. "I'm committed to McKechnie," Fuchs said. "He's a most satisfactory manager and can stay with me as long as he's in baseball." However, the more the judge thought about it, the more he liked the idea of Babe Ruth in a Braves uniform.

Babe Becomes a Brave

There were some snags. Babe had stated he would never sign another player contract unless he could also manage, and Jacob Ruppert had said he would never release him to play for another team. Yankees general manager Ed Barrow simply wanted Ruth gone for good, and so he worked out a plan that would make everybody happy.

"I'm ready to make an offer for Ruth," Fuchs said in Boston after the scheme had been devised. "We will make him assistant manager and give him an official position if he comes to the club, and he can play as often as he likes."

Nobody bothered to ask then what an assistant manager was or did, but Babe suddenly seemed interested in playing baseball again. Talking with reporters the day the S.S. Manhattan docked in New York, returning him from his Asian baseball exhibition adventures, he spoke mysteriously of "having something under consideration that I can't talk about right now.... All I can say is, it has to do with big league baseball."

The fish was hooked. The next day Ruth spoke to Ruppert to get a further understanding of the Braves offer, then telephoned Fuchs for final details. As Fuchs explained it to him, Babe would be a vice president of the Braves, sharing in organizational profits, and with a first option to buy club stock.

He would also be assistant manager to McKechnie, and in a year or perhaps earlier he would take over as manager when Bill moved up to general manager. Babe would be a regular player when he felt able and a pinch hitter the rest of the time. His base pay would be $25,000 -- more than anyone on the team including McKechnie.

Everything was put down in a lovely letter the judge sent to Ruth the following day, a letter that gave new meaning to the term "double-speak" and, in effect, promised Babe nothing but a straight player contract. The letter Fuchs sent follows:

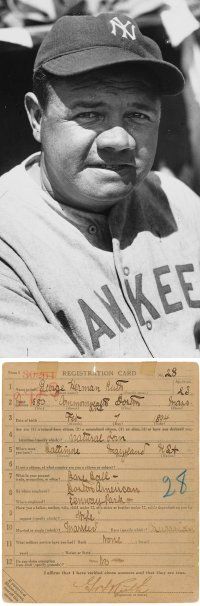

Mr. George H. Ruth, New York, N.Y. February 23, 1935

My Dear George:

In order that we may have a complete understanding, I am putting in the form of a letter the situation affecting our long-distance conversation of yesterday.

The Boston Braves offer you the following inducements, under the terms and conditions herein set forth, in order to have you sign a uniform contract plus an additional contract which will further protect you, both contracts to be filed.

1. The Boston club offers you a straight salary contract.

2. They offer you an official executive position as an officer of the corporation.

3. The Boston club offers you also the position, for 1935, of assistant manager.

4. They offer you a share of the profits during the term of this contract.

5. They offer you an option to purchase, at a reasonable figure, some of the stock of the club.

6. The details of the amounts agreed upon will be the basis of a separate contract which shall be a personal one between you and the club, and, as the case may be, with the individual officials and stockholders of the club.

In consideration of this offer, the Boston club naturally will expect you to do everything in your power for the welfare and interest of the club and will expect that you will endeavor to play in the games whenever possible, as well as carry out the duties above specified.

May I also give you the picture as I see it, which, in my opinion, will terminate to the best and mutual interest of all concerned.

You have been a great asset to all baseball, especially to the American League, but nowhere in the land are you more admired than in the territory of New England that has always claimed you as its own and where you started your career to fame.

The fans of New England have a great deal of affection for you, and from my personal experience with them are the most appreciative men and women in America, providing, of course, that you keep faith, continue your generous cooperation in helping civically and being a source of consolation to the children, as well as to the needy, who look up to you as a shining example of what the great athletes and public figures of America should be.

I say frankly, from my experience of forty years interest in baseball, that your greatest value to a ball club would be your personal appearance on the field, and particularly your participation in the active playing of exhibition games, on the ball field in championship games, as well as the master-minding and psychology of the game, in which you would participate as assistant manager.

As a player, I have observed and admired your baseball intelligence, for during your entire career I have never seen you make a wrong play or throw a ball to the wrong base, which leads us to your ability to manage a major league baseball club. In this respect we both are fortunate in having so great a character as Bill McKechnie, our present manager of the club, who has given so much to baseball and whom I count among my closest friends. Bill McKechnie's entire desire would be for the success of the Braves, especially financially, as he is one of the most unselfish, devoted friends that a man can have.

That spirit of McKechnie's is entirely returned by me, and I know by my colleagues in the ball club. They feel, as I do, that nothing would ever be done until we have amply rewarded Manager McKechnie for his loyalty, his ability and sincerity, which means this, George, that is it was determined, after your affiliation with the ball club in 1935, that it was for the mutual interest of the club for you to take up the active management on the field, there would be absolutely no handicap in having you so appointed.

It may be that you will want to devote your future years to becoming an owner or part owner of a major league ball club. It may be that you may discover that what the people are really looking forward to and appreciate in you is the color and activity that you give to the game by virtue of your hitting and playing and that you would rather have someone else, accustomed to the hardships and drudgery of managing a ballclub, continue that task.

So that if we could enter into the spirit of that agreement, such understanding might go on indefinitely, always having in mind that we owe a duty to the public of New England that I have personally learned to love for its sense of fairness and loyalty, and it is also in this spirit that I hope we may be able to jot down a few figures of record that will prove satisfactory to all concerned.

Sincerely yours,

Emil E. Fuchs, President

Ruth never showed this monstrosity to a lawyer, nor did he pick up on its subtle loopholes. After asking Ruppert one more time if McCarthy was the best man to manage the Yankees (the colonel assured him he was), Ruth decided to take the offer.

Ruth's New Position

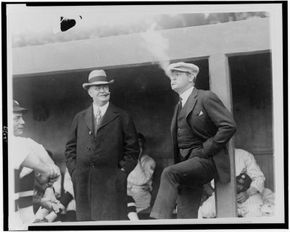

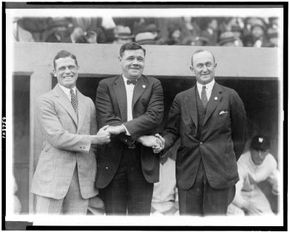

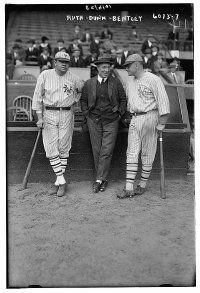

Babe Ruth and Ruppert went to Boston to finalize things with Fuchs, then the three met with the New York press the next day to talk sweetly of each other and make the deal official. Speaking of how they had "always been friends," Ruppert handed Babe a piece of paper on which were 16 words that set Ruth on the path to oblivion:

"Mr. George H. Ruth: You are hereby notified as follows: 1. That you are unconditionally released. (Signed) Jacob Ruppert."

Babe later said in his autobiography that the process of having a 15-year relationship with the Yankees severed in such a staged manner "made me a little sick," but on this day there was nothing but smiles all around.

Ruth paused when he was asked what his role would be as vice president, and Fuchs chimed in by saying he would be "consulted on trades and so forth." The colonel couldn't help getting in a little dig of his own. "A vice president signs checks," he spouted, and the room erupted with laughter.

Reached in Boston, a suddenly supportive Tom Yawkey predicted the move would be "of great benefit to a great baseball city -- one which surely can support two baseball teams and support them well."

It was just six days since Ruth had returned from his trip. While he was sad to be leaving New York, he had every reason to believe his new position in Boston was the beginning of a great new career that would prove as successful -- and profitable -- as the first.

Asked if he and McKechnie might have a rocky relationship, the Babe said, "I'm sure we'll get along lovely," before breaking into more talk of his own pending managerial career.

There was more doublespeak from Fuchs at a huge Boston dinner in Babe's honor a few days later. All of this verbal runaround did little to deter the Babe's enthusiasm over his multiple roles, but then came a rather ominous reply from McKechnie:

"The Babe would help any ball club. But I'm interested in him only as a player. He wouldn't be worth a plug nickel to us if he didn't get into uniform and go up there to bat." When one Boston Globe headline read rather prematurely "Babe Ruth to Manage Braves in 1936," McKechnie had a simple answer for that as well: "That's news to me."

The Return to Boston

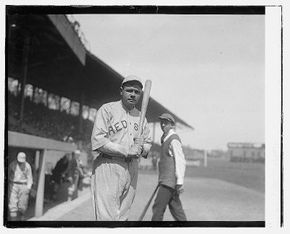

It had now been 21 years since a Baltimore train had brought the big 19-year-old youth into Back Bay Station. Now, George Herman Ruth Jr. was returning to Boston.

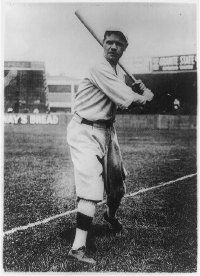

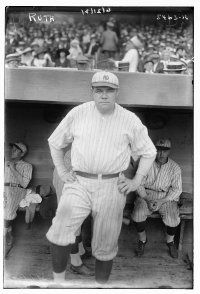

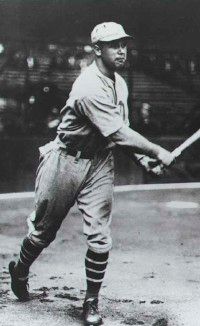

There had been no winter workouts at Artie McGovern's gym, and Ruth reported to spring training in St. Petersburg (and 3,000 frenzied fans at the train station) weighing 245 pounds and in poor shape. Photographs from his first days with the Braves show his stomach sticking out as if someone has stuck a medicine ball under his sweatshirt, and after a while someone realized it would be wiser if Babe kept his uniform on at all times.

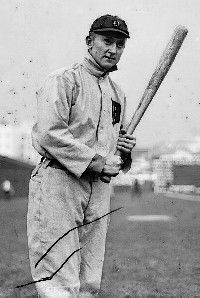

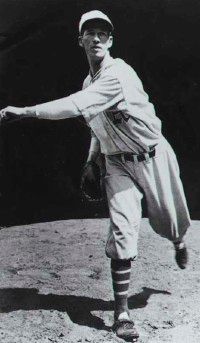

The uniform itself, white with red trim and the large Braves' logo in the center, looked strange after so many years in regal pinstripes. The team didn't even have a new one big enough for him, and Ruth had to make due with an ill-fitting hand-me-down from robust catcher Shanty Hogan.

Just as his first days with the Yankees had brought new life to New York's spring training, Ruth drew huge crowds and media attention wherever he went with the Braves. A March 16 battle with his former club in St. Petersburg was played before the largest gathering of fans ever to see an exhibition in Florida.

The Babe, however, hit no homers then or at any time the first month of camp. The revitalization seen in Japan had been a false sign; Ruth didn't belong in the outfield and wasn't producing at the plate. McKechnie used him at first base in place of holdout Baxter Jordan. He didn't look much better there, but at least he didn't have to run.

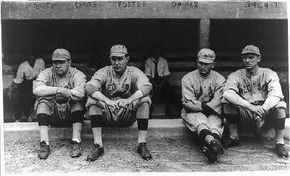

Even Ruth later admitted his performance was frustrating: "The kids were striking me out or making me pop up... It was a rotten feeling." About the only fun he had other than talking about his pending managerial position was bumming around with the club's 43-year-old shortstop Walter "Rabbit" Maranville, a 5' 5", 155-pound pixie who matched Ruth's appetite for adventure and was also nearing the end of the line. On a club of mostly journeymen, the two old-time stars could relate to one another.

Relating to McKechnie was another story. The manager was getting sick of all the attention the Babe was getting -- especially since Ruth kept yakking about taking over his position. Besides, Bill had no idea where he was going to put the Babe once Jordan signed. When somebody asked McKechnie for the umpteenth time what Babe's leadership role on the team would be, he snapped back, "Ruth's title as assistant manager means nothing particularly."

Ruth on the Field

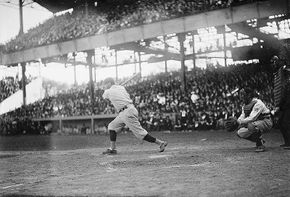

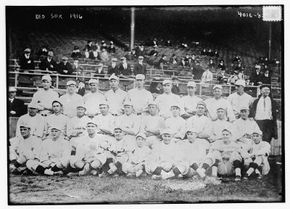

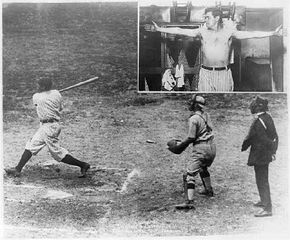

Babe showed a little life with three exhibition homers as the club headed north. He was starting in left (Baxter had signed) when Boston opened the regular season against the Giants at Braves Field on April 16, 1935.

It was Babe's first time playing there since he had pitched the Red Sox to a 2-1, 14-inning victory over Brooklyn in the 1916 World Series, and 22,000 fans, including five New England governors (the largest Opening Day crowd in the park's history), braved 39 degree temperatures to see if he could rise to the occasion again.

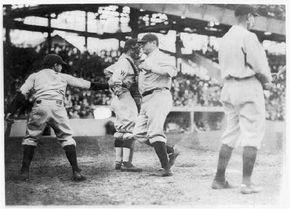

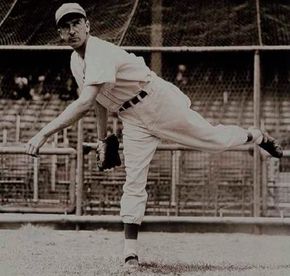

On the mound for New York was his old chum Carl Hubbell -- he of the five consecutive All-Star strikeouts. Hubbell was coming off a 21-12 season and was arguably baseball's best pitcher. When the portly 40-year-old Ruth stepped to the plate with one runner on in the first inning, it looked like a pure mismatch.

It was. Ruth lined a single to right to drive in Boston's first run, then scored its second a few moments later. The score was still 2-0 when Hubbell came to the plate in the top of the fifth with a man on, and when he lined a shot to left, Babe made a great one-hand catch while running past the foul line.

Babe was up again with a man on in the bottom of the inning. This time he smashed a Hubbell screwball into the right field bleachers for his first National League homer and a 4-0 lead. Boston claimed a 4-2 victory, and Ruth echoed the thoughts of many when he said of the performance, "I didn't dream I'd ever get off to such a start."

The city went nuts, especially when Ruth added two more hits in the second game. The Braves were going all the way, folks surmised, and the Babe was going to lead them there. It was great newspaper copy, but it was also pure fantasy.

Ruth was in no condition to be a savior, and this was no championship club. Berger was a fabulous slugger (especially considering his home park's dimensions), but other than him there were no legitimate stars. It was a mediocre club at best, and distractions caused by Babe's presence made it difficult for McKechnie to maintain control and seemed to affect the team's on-field play.

Bill didn't know it, but he wouldn't have to worry about the distraction for long. In the next month Ruth had just two more hits (one of them a homer against the Dodgers on Easter Sunday), and his average fell well below .200. He missed several games with a cold and various other ills. The club had already settled deep into the second division by this point, and the few fans who came to Braves Field booed unmercifully as reality set in.

Babe's profit sharing situation wasn't looking very good, and neither was his supposed leadership role on the club. As a vice president, he seemed to hold no duty more important than that of a greeter and front office puppet. An increasingly perturbed McKechnie sought no advice from his "assistant manager" as the team wallowed near the cellar.

Soon the whole scheme became apparent to Ruth; McKechnie wasn't going to be moving up to general manager, and he wasn't going to be taking Bill's place. The entire contract and Fuch's letter had all been a public relations scam.

The realization was unsettling for the Babe. He had given the major leagues over 20 years of his life, saved baseball from extinction following its greatest scandal, and was now being denied a chance to stay in the game on his own terms. For the greatest hero in American sports history, it didn't seem a fitting epilogue.

But an epilogue it was, as Babe Ruth was not far from retirement. Learn how he left the game on the next page.

For more information about baseball and baseball players: