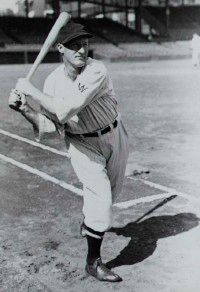

Babe Ruth's 1923 and 1924 Seasons

When the 1923 baseball season began, Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees led the American League from Opening Day. After the middle of June, no club was within five games of them. They finished 16 lengths ahead of second-place Detroit.

The Red Sox were 37 games back, seven games out of seventh place. Attendance around the American League was down. Fans became bored with how easily the Yankees quashed the opposition.

Advertisement

Ruth's 1923 Stats

As a batter, Ruth was merely sensational. He led the AL in seven categories, including on-base percentage and slugging average. He walloped a dozen more homers than the runner-up. His batting average was .393, the highest mark of his career and second only to Harry Heilman's .403.

The strategy of taking the bat from his hands didn't work; with all that offensive firepower, he still walked 170 times. No batter has ever walked more in one season. The next closest man received 72 fewer free passes. Ruth won the Most Valuable Player Award hands down. There is debate about which of Ruth's seasons was the most impressive overall, but Ruth told a biographer that to him 1923 was his "peak year."

The 1923 World Series

The World Series pitted John McGraw's Giants against Ruth and the Yankees once again. McGraw took the unusual step, for the time, of calling all the pitches his hurlers threw to Ruth. He explained it by saying, "Ballplayers can do a more workmanlike job when they feel someone else is taking the responsibility."

The Yankees lost Game 1 by one run (5-4) when Casey Stengel hit an inside-the-park home run in the top of the ninth inning. As Stengel was rounding first, a pad in his shoe meant to protect a sore heel slipped loose. Stengel thought his shoe was coming off, so his usual speedy step was thrown askew. The description of his gait by Damon Runyon in the next day's newspaper has become a baseball classic.

Counting this defeat in Game 1, the Yankees had lost eight consecutive Series games to the Giants: the last three in 1921 when Ruth was out with the abscessed elbow followed by the 1922 four-game sweep. Things were about to change.

In Game 2 of the 1923 Series, Ruth belted two homers. The first blast went over the Polo Grounds rightfield roof, and the second helped the Yankees to a 4-2 victory.

Stengel won Game 3 (1-0). Again a home run provided the punch, this one heading over the fence. When he thumbed his nose at the Yankees bench as he rounded third, the Yanks pretended to be aghast. They asked Judge Landis to take action. The commissioner commented, "When a guy hits two home runs to win two World Series games, he deserves a little fun."

Stengel, as fate would have it, provided the only excitement for Giants fans in the Series. The Yanks exploded for six runs in the second inning of Game 4, scored seven in the first two frames of Game 5, and blew open a tight match in Game 6 with five runs in the eighth.

The Yankees were world champions for the first time. In his 19 times at bat, Ruth hit three homers and scored eight runs. McGraw's pitch-calling walked him eight times. With an overall attendance of 302,000 for the six games, gross receipts reached $1 million. The Yankees each took home $6,160.46 for their win; the Giants $4,112,81. That record stood until 1935.

Babe the Big Kid

The Babe still loved being with kids. Lots of them. During his annual postseason barnstorming tour, 6,000 kids swarmed onto the field after one game, flattening the superstar. They continued piling on their hero until four police officers were able to clear them off. The laughing Babe arose uninjured and wanted to throw baseballs to them, but the cops, fearing a riot, refused.

During spring training of 1924, Jocko Conlan (later to earn fame as a major league umpire) was a player with the Rochester Red Wings in the middle of an exhibition series with the Yankees. Conlan tells this story:

"At Mobile there was a large crowd. After the game the teams went to their hotel and had dinner and Ruth still hadn't come back [from the game]. He finally came in about eight o'clock without his cap; his shirt was torn, his fielding glove was tied to his belt with a cord, and his baseball suit was all muddy with Alabama clay up above his knees.

The reporters asked Ruth, 'Where were you?' Ruth said, 'There were about 75 kids who stayed in the park and wanted to play ball. I spent all the time since the game hitting flies and shagging flies with the kids.'"

The 1924 Season

As had become his custom, Ruth reported to Hot Springs to sweat and golf off the extra pounds the winter had added to his frame. He was about 240 when the recurrent spring flu got him again. Burning with fever, he sweated off 22 pounds in a few weeks.

The biggest news Babe made during spring training that year was losing a $1,000 bill somewhere between the team's hotel and the bank. He had four of them to start with.

The 1924 season was dismal for the Yankees. The team was aging; four regulars and nearly all their bench were over 30. That didn't keep them away from the speakeasies and parties; they were as boisterous a bunch of noisemakers as ever. Their performances, however, slipped drastically. Except for the Babe.

He may have been leading the party brigade, but at age 29, Ruth had plenty of life in him to burn the candle at both ends. In fact, 1924 is the first year that Ruth biographers mention his frequent use of bicarbonate of soda to quell the rumblings of an overfed stomach.

For Babe, the bubbly drink was just what the doctor ordered. He'd revel throughout the night, then before each game, down a few hot dogs and several bottles of soda pop, drink some bicarb, emit a Ruthian belch, and go merrily on his way.

The players' tempers weren't calmed by their escapades off the field. Ruth was at the center of an on-field brawl with Ty Cobb. The fray led to several ejections and fines, and the forfeiture of the game to the Yankees when angry Detroit fans stormed the field. The team was out of control, and nothing manager Mitchell Huggins could do seemed to make any difference.

He shipped off one of his more surly (though highly talented) pitchers, Carl Mays, to Cincinnati in midseason, and the Yanks never recovered. After starting the season hot, the Yankees fell behind the surging Washington Senators. Without Mays, the Yanks were unable to catch up and finished two games back. The Senators' late charge, winning 16 of their final 21, made the difference.

Ruth kept his sense of humor. Perhaps nothing would top the event that happened just the summer before. It was a very hot day, and the team was to meet President Harding before a game. When it was Babe's turn to shake his hand, he stopped, wiped his huge brow with a huge handkerchief, and said, "Hot as hell, ain't it, Prez?"

Ruth finished the season by winning his first and only batting title. He won the home run title again and led the league in runs, total bases, walks, on-base percentage, and slugging average. Goose Goslin of the Senators wound up driving in 129 runs to Babe's 121, and Babe didn't win the Triple Crown. (He never would.)

The Babe's most successful barnstorming tour ever took place that fall. His and Bob Meusel's teams traveled 8,500 miles and played in 15 cities before 125,000 people. Out of 15 games, Babe's team won every one; he also hit 17 homers.

According to biographer Marshall Smelser, in 1924 Babe Ruth's signature appeared on 10,000 balls and 2,000 bats. He had taught the Yankee trainer how to forge his signature.

A series of illnesses would plague the Babe in the coming years. Learn more in the next section.

For more information about baseball and baseball players:

- Baseball

- Minor League Baseball

- Baseball Hall of Fame