Babe Ruth's Comeback

After the 1925 season, it was hard to find a sportswriter -- or anyone, for that matter -- who didn't view the career of Babe Ruth as over.

He was 31 years old, and an "old 31," as sports columnist Fred Lieb had said. He had already set a barrel full of batting records, with 356 career home runs, over 1,000 career RBI, and a batting average of .345. If the experts of the time had been right in their assessment that he was through, Ruth would still merit a spot on many all-time teams.

Advertisement

But they were dead wrong. No one of his time really seemed to understand Ruth. They had overestimated his maturity in his earlier years, and they underestimated it in 1926. Ruth was still growing up, still becoming the man that Brother Matthias saw in him 25 years before -- and he had a major comeback in store.

Ruth's New Regimen

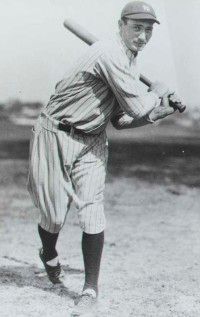

Ruth decided he needed to get in shape. He put himself under the punishing care of Manhattan gym owner Artie McGovern. McGovern was a stern taskmaster. Upon his arrival, Babe weighed in, tipping the scales at a portly 256 pounds. By the time he left for spring training, he was a slender and powerful 212.

With four-hour workouts every day and strict supervision of Ruth's diet, McGovern had the Babe looking and feeling like the "keed" who had torn baseball apart in 1920 and 1921. Ruth's blood pressure improved; he lost nine inches off his waistline and six off his hips. By mid-January he had to order a whole new shirt wardrobe; the collars on his old ones were too large.

The 1926 Yankees

The 1926 Yankees were a team of potential but with a host of question marks. They had two rookies at the vital keystone positions: Mark Koenig and Tony Lazzeri. Lazzeri was already a bit of a legend himself. At that time, he was the only person in professional baseball history who had hit more home runs in a season than Babe Ruth.

In 1925, over the course of 197 games in the Pacific Coast League, Lazzeri had belted 60 homers. As a rookie, Lou Gehrig had established himself at first, but his .295 batting average and 20 home runs were hardly legend material (not yet, anyway). The pitching staff was downright old. Waite Hoyt, at 26, was the youngest starter (the next in line was six years his senior).

When the Yankees lost their first two spring training games to the Braves by a total of 28 runs, the "experts" jumped on the bandwagon. They were still wearing egg on their faces for predicting the 1925 team would finish first before it finished seventh. Writer Westbrook Pegler trumpeted that the 1926 Yankees were "the worst team he ever saw" and were "sure to finish in last place."

What these prognosticators did not know was that the team was beginning to jell. The pitching was surprisingly effective and was bolstered by what would become one of the great offensive units of all time. The Yanks ended spring training with an 18-game winning streak, the last dozen being played against the Dodgers as the two teams traveled north together.

Instead of holding their predicted last-place berth, the 1926 Yankees were never even in second place. A 16-game winning streak stretched their lead to six games and growing by June 1. On September 25, Ruth, Gehrig, and Bob Meusel homered in succession.

The trio's accomplishment marked the first time that had happened in the majors in 23 years. The Cleveland Indians, led by ace hurler and Ruth nemesis George Uhle, charged in August and September while the Yanks cooled off, allowing the Tribe to finish only three games back.

The Yankees' team ERA was only fourth in the league, but they outscored every other team by at least 45 runs. The spry young Gehrig led the league with 20 triples and added 16 homers to go with his .313 batting average.

Lazzeri pitched in with 14 triples and 18 homers, and Meusel, despite breaking a bone in his foot and playing just 108 games, swatted a dozen homers and drove in 81. As a team, the Yanks were second in batting average but easily led the AL in on-base percentage and slugging average.

Ruth and Brother Matthias

Ruth, meanwhile, had the kind of season everyone had predicted he never would have again: leading the league in homers with 47, runs scored, RBI, and walks, and finishing second in batting average. To demonstrate that he was a team player, he laid down 10 sacrifice bunts, too. The sweat in McGovern's gym had paid off.

A figure from Ruth's past helped, too. In June, Chicago was the site of the International Eucharistic Congress, a huge gathering of devout Catholics. The Yankees were in town at the same time, and they wisely invited Brother Matthias to join them from Baltimore.

Ruth had dinner with Matthias, and his surrogate father did what fathers are supposed to do: He delivered a personal sermon to the Babe on the evil of his ways. Ruth took it to heart, at least for a while. His marriage to Helen was definitely over, the Sudbury farm had been sold, and she and Dorothy had moved to Boston. The last public appearance of the three together was at that year's World Series.

The 1926 World Series

In that fall classic, the Yankees faced the Cardinals, another offensive powerhouse, led by player-manager Rogers Hornsby, perhaps the greatest right-handed hitter of all time. Game 1, however, was a pitcher's duel between Redbird Billy Sherdel and Yank Herb Pennock. The score was tied 1-all in the last of the sixth when Ruth led off with a single, was bunted to second by Meusel, and scored the winning run on Gehrig's single.

In Game 2, the 39-year-old alcoholic, epileptic pitching legend Grover Cleveland ("Pete") Alexander held the Yanks to four hits and won 6-2. The teams moved to St. Louis, and Jesse Haines mastered the Yanks in Game 3, shutting them out on five hits.

Game 4 was the stuff of legend. The first two Yanks struck out, but Babe slugged a home run off Flint Rhem on the first pitch he saw. He homered again in the third inning.

This game, sent over the airwaves through a 33-station radio network, was the first Series game ever broadcast nationally. Booming-voiced Graham MacNamee's call when Ruth batted again in the sixth against Hi Bell was truly exciting and is worth repeating, for several apparent reasons. MacNamee's words follow:

"The Babe is up. Two home runs today...Babe's shoulders look as if there is murder in them down there, the way he is swinging that bat.... That great big bat of Babe's looks like a toothpick down there, he is so big himself.... Three and two. The Babe is waving that wand of his over the plate. Bell is loosening up his arm. The Babe hits it clear into the centerfield bleachers for a home run! For a home run! Did you hear what I said? Where is that fellow who told me not to talk about Ruth anymore? Send him up here. Oh, what a shot! Directly over second.... Oh, what a shot! Directly over second base far into the bleachers out in center field, and almost on a line and then that dumbbell, where is he, who told me not to talk about Ruth! Oh, boy! Not that I love Ruth, but, oh, how I love to see a shot like that! Wow! That is a World Series record, three home runs in one World Series game, and what a home run! That was probably the longest hit ever made in Sportsman's Park. They tell me this is the first ball ever hit in the centerfield stands. That is a mile and a half from here. You know what I mean."

Ruth scored four runs and drove in four as the Yankees romped to a 10-5 win. Another pitchers' duel ended after 10 innings the next day with the Yankees on top 2-1. The teams returned to Yankee Stadium for Game 6, and Alexander spun his magic again, holding Ruth hitless and winning 10-2.

Game 7 was a struggle. Babe's third-inning homer gave the Yankees a one-run lead, but the Cards pushed across three in the top half of the fourth. Receiving his ninth walk of the Series in the fifth didn't help Ruth, even though it broke his old Series record. (He would walk twice more in the game.) A run in the sixth brought the Yanks within one.

In the last of the seventh, Combs led off with a single and was bunted to second. Ruth was intentionally passed, and after a force-out, Gehrig also walked, loading the bases with two down. Hornsby called in the rocky veteran Alexander to pitch to the rookie Lazzeri. (Lazzeri, coincidentally, also had epilepsy.)

Some said that Alexander had celebrated his win the day before a little too much and was severely hungover or maybe even still drunk. Hornsby stared into Alexander's eyes and was satisfied with what he saw. Without having thrown a pitch in the bullpen (to conserve the energy left in his aging arm), Alexander struck Lazzeri out.

Alexander also made quick work of the three Yankees he faced in the eighth and had put the first two down in the ninth when Ruth came to bat. Pitching carefully to the slugger, Alexander walked him on a 3-2 count. Alexander was sure that the pitch the ump called ball three was really strike three. He felt the same about ball four. After one strike to Bob Meusel, Ruth lit out on an attempted steal of second. Bob O'Farrell threw him out easily, ending the Series with a stunning surprise.

Although Ed Barrow and others felt Ruth's attempt was a stupid play, Ruth didn't. His logic makes sense: getting into scoring position with two out would greatly help New York's chances of tying the game. In addition, Ruth wasn't slow; he had swiped 11 bases during the season, and he had already stolen one base against O'Farrell the day before. Although this was the Yankees' third World Series loss in four appearances, they would win eight more before they lost again.

A Ruth Legend

One of the most enduring stories created by sportswriters about Ruth had its origins during this Series. A sick boy named Johnny Sylvester lay on his deathbed, severely injured in a fall from a horse. Ruth visited him in the hospital and promised to hit a home run for the dying boy that day.

That was the afternoon Ruth slugged not one, not two, but three homers. The boy recovered, and someone decided that Ruth's home run prowess had saved little Johnny's life. Years later, the now-grown boy showed up and thanked the Babe for all he had done, and the two wept in joy.

Great story, but the facts are these. Sylvester's dad wired Ruth from New Jersey, where the family lived, during the Series and asked for an autographed ball. The Yanks and Cards each sent one along. The sick kid was grateful, although no one promised him a home run.

After the Series, while Ruth was barnstorming, he showed up at the Sylvester's home one day on an impulse. Ruth and Johnny chatted. A year later, Johnny's uncle met Ruth and thanked him for all he had done for the sickly little lad. The Babe smiled graciously and asked how Johnny was doing. He then turned to a friend and said, "Now who... [is] Johnny Sylvester?"

That year's barnstorming routine was a hit. Ruth also performed as a solo act in vaudeville on a 12-week tour that earned him $65,000.

Shortly thereafter, the 1927 baseball season began. Learn more about Babe Ruth's performance on the next page.

For more information about baseball and baseball players:

- Baseball

- Minor League Baseball

- Baseball Hall of Fame