Babe Ruth's Barnstorming

The word "barnstorming" arose from old vaudeville days when shows went on the road and were willing and eager to play anywhere -- even in a barn. Baseball teams had done it since the 1860s, and Babe Ruth was a big fan of this fun and moneymaking off-season prospect.

Albert G. Spalding had led a world-wide barnstorming expedition in the 1870s. It was a great way to make extra money without hard work. Fans who couldn't normally see major league players loved the games, the players had fun playing them, and all seemed to work out well. In fact, the first "World Series," in the 1880s, was just such postseason baseball tours.

Advertisement

However, by 1914 owners weren't so keen on the idea. First, they didn't make any money on the deal; the players did. Second, the players might get hurt. Barnstorming also diminished the importance of their own official post-season championships, as the two pennant winners could sign up with local promoters to "replay the World Series" on tiny fields across the country. However, no one from organized baseball had stepped forward to enforce the rule stringently.

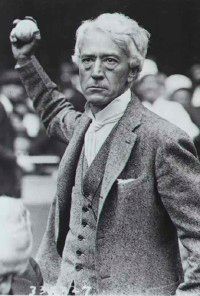

Baseball Commissioner Landis

Enter Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Landis, a federal judge without a genuine law degree (not uncommon at the time), was a braggadocio "enemy of the trusts," whose rulings were usually overturned by higher courts.

The judge, who loved baseball, had heard the Federal League's suit against the majors and judiciously refused to make a ruling until the Feds collapsed under their own weight. His inaction earned Landis the undying gratitude of the major league owners.

When the "Black Sox" scandal broke in 1920, mutally destructive strife among the owners kept them from taking forceful action. So they appointed Judge Landis to the post of Commissioner and gave him supreme power to act in the best interest of the game.

Landis certainly looked the part, with the craggy, imperious visage and stern, morally inspired, withering stare. He took the owners at their word: He did whatever he felt was best for baseball. He tossed eight members of the suspected (but not convicted) White Sox out of the game forever.

Other players who brought with them the slightest whiff of improper behavior were dismissed. Even owners felt his wrath; he ordered Charles Stoneham and John McGraw to sell off their gambling interests.

Landis vs. Ruth

When Commissioner Landis heard that Ruth, Bob Meusel, and a few others were planning to take their show on the road, he acted instantly, calling Ruth to command that he stay home. Ruth, not surprisingly, refused. He was on his way to catch the train that would take him to Buffalo, first stop in the tour.

"Oh, you are, are you? That's just fine. But if you do, it will be the sorriest thing you ever did in baseball," the enraged judge shouted before he slammed down the receiver. He proceeded to rail at length about the young Ruth's boldness in gutter language.

Landis saw the World Series as his domain, and he desperately needed to establish the legitimacy of that Series as a championship, not just another exhibition. Anyone trying to challenge that was defying him personally.

Ruth wasn't intimidated. What could Landis do -- refuse to pay him his World Series share? The fact is, playing the World Series cost Babe Ruth money. A good barnstorming tour could put $25,000 in his pocket.

Landis laid down the law in frighteningly direct terms: "This case resolves itself into a question of who is the biggest man in baseball, the Commissioner or the player who makes the most home runs." Ruth's bosses, Huston and Ruppert, quietly concurred with the chief.

The tour didn't make much money. Bad weather rained out many games. Other cities feared Landis's wrath and cancelled. Many minor league teams, also cowed by the commissioner, forbade the barnstormers to use their fields.

The baseball barnstorming over, Ruth went on a vaudeville tour with performer Wellington Cross. The biggest laugh of their act came when a "messenger" delivered a "telegram."

Ruth said his line, "It's from Judge Landis."

Cross would then respond, "Is it serious?"

"I'll say," Ruth replied. "Seventy-five cents, collect."

Landis waited until December to hand down his rulings. He withheld World Series shares from Ruth and Meusel and then suspended them from playing until May 20, 1922. It would cost them each 39 days without pay. Ruth was advised to beg for leniency. He went quail hunting instead.

The Babe Muddles Through

Although an athlete of rare proportions, the 26-year-old Ruth was still an adolescent emotionally. He was good-hearted -- with his first 1922 paycheck he bought a Cadillac for St. Mary's -- but confused.

Imagine the poor Babe's emotional muddle. Here he was, a supremely gifted athlete playing the game he loved most dearly at a level of profound excellence no one had ever seen before. His awesome physical skills were at their peak. He was making money no ballplayer had ever approached, more money in one season than most Americans would see in 10 years of work.

Early in 1922, he signed a three-year contract for $52,000 a year, more than three times as much as the next highest-paid Yankee. (The story goes that the extra $2,000 was determined by a coin flip because Babe "liked the idea" of making a thousand dollars a week.) He was earning that much again in outside deals, endorsements, vaudeville, and barnstorming.

Yet here he was, banned from playing baseball. Banned from doing what he did best (not to mention better than anyone else), and banned from making money at it. The reason?

He had played baseball and made money at it.

Spring Training 1922

Interestingly, the ban of Ruth and Meusel did not apply during spring training. Ruth had singlehandedly turned the expected dollar losses of southern spring workouts into positive cash flow for the team. People paid to see the big lug, no matter where it was. So the team made money.

Some say the Yankees made enough on spring training ticket sales to pay Ruth's salary for the entire season. The imperious Landis had no qualms about penalizing the boy-man and his cohort for disobedience, but he could not see fit to take money out of the ample pockets of Ruppert and Huston.

During the spring, Landis made a trip to New Orleans (a curious place to locate spring training for a high-living bunch like the Yankees). There, Ruth and Meusel met with him to plead their case for early reinstatement. Landis had already received a petition signed by 10,000 New Yorkers begging for just that.

When the two players left, apparently having heard both barrels of a full-blown Landis diatribe, only Babe could speak. His comment: "That guy sure can talk." That night Landis attended a charity game and auction. He proceded to outbid everyone ($250) to win a Ruth-autographed baseball.

But Landis wanted more than contrition. He wanted a promise that Ruth would never go on off-season barnstorming tours again. Unless, of course, they were tours from spring training north, in which the Yankees would make most of the money.

Ruth bristled against that idea until Huston asked him, "What would happen to the Yankees if you and Meusel got suspended for a whole year?" The Babe saw the light. He was also named captain, a largely honorary title, but one that meant much to him.

Despite his title, however, Babe Ruth's next season was not his finest hour. Find out what happened on the next page.

For more information about baseball and baseball players:

- Baseball

- Minor League Baseball

- Baseball Hall of Fame