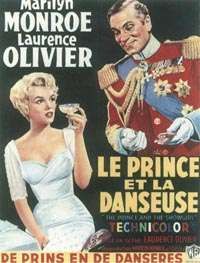

Marilyn Monroe in 'The Prince and the Showgirl'

Less than two weeks after their marriage, Marilyn and Arthur Miller departed for London, where she began work on her new film, a version of Terence Rattigan's play, The Sleeping Prince.

Scheduled to produce and direct the sophisticated comedy was England's most celebrated actor, Laurence Olivier, who was also slated to star in the title role opposite Marilyn. Included among the distinguished supporting cast was Dame Sybil Thorndike.

Advertisement

The contracts involving The Sleeping Prince had been signed in February of 1956. At that time, Olivier had flown to New York to join Marilyn for a press conference to announce his plans.

Almost 200 reporters showed up for the event. The atmosphere was highly charged, not only because of the presence of Marilyn and Olivier, but also because the bustle of activity was confined to a too-small room.

After the questions commenced, one of the thin shoulder straps on Marilyn's black velvet dress broke, causing a sensation and diverting attention away from Olivier and the proposed film.

A cynical press, more hostile toward Marilyn during this period than usual, accused her of intentionally breaking the strap. Marilyn denied the charge, angrily retorting, "How would you feel if something of yours broke in front of a whole room full of strangers?"

Years later, Olivier would also contend that Marilyn's strap broke by design, not by accident. Whatever the case, Olivier got a telling preview of what working with Marilyn would be like, particularly in terms of the chaos related to her publicity and the tension generated between her desire to be a serious actress and her image as a movie star.

The film version of The Sleeping Prince, later retitled The Prince and the Showgirl, was the first independent project undertaken by Marilyn Monroe Productions. Milton Greene had purchased the property especially for Marilyn, and the unlikely team of Monroe and Olivier caused some chuckles in the press.

Greene accompanied the Millers to London, as did Paula Strasberg and secretary Hedda Rosten. Olivier eventually clashed with all members of the Monroe entourage, though he managed to remain affable with Greene.

Problems began on the set almost immediately. Olivier had heard of the difficulties working with Marilyn and had sought the advice of her former directors, including Joshua Logan.

Logan advised Olivier not to be commanding or domineering and not to raise his voice in anger; to do so would cause Marilyn to lose her confidence and thus her ability to work. Logan also reassured Olivier that Marilyn's performance would be worth any effort.

Whether Olivier did not fully grasp the meaning of Logan's advice or whether his temperament could not handle the frustration of working with such an insecure actress, he quite quickly brought out the worst in Marilyn. He could not comprehend her tendency to become distracted while taking direction, which he mistook for rudeness or denseness.

He became frustrated with his costar, often raising his voice in anger and occasionally insulting her. Marilyn responded by arriving on the set hours late, sometimes failing to show up at all.

Her tardiness was not the result of any vindictiveness on her part but was due to her innate fear and insecurity, which was heightened by Olivier's authoritative demeanor. Marilyn's fear of performing in front of Olivier and the other seasoned English actors in the cast virtually paralyzed her, a condition she sought to alleviate through prescription drugs.

Other disagreements developed from the presence on the set of Paula Strasberg, for whom Olivier had little respect as a coach. Olivier's approach to acting was the direct opposite of the Strasbergs' Method.

A classically trained stage actor who tended toward impressive but conservative interpretations of Shakespeare, Olivier maintained a lifelong skepticism for the psychological undertones of the Method.

Thus, in addition to any personality conflicts Olivier may have had with Marilyn, there were fundamental differences between the two in terms of how they approached their craft.

Paula Strasberg returned to the States before production was completed. Conflicting accounts of the episodes leading up to her departure blame her abrupt disappearance on everyone from Olivier to Miller. Strasberg eventually returned, and Marilyn's analyst was flown in to help her cope with the mounting tension on the set.

Less sympathetic accounts of the behind-the-scenes turmoil tend to place blame on the Monroe camp. But to do so oversimplifies the situation.

Olivier had directed only a handful of films prior to The Prince and the Showgirl, all of them adaptations of plays by Shakespeare. He was accustomed to directing classically trained actors and actresses much like himself.

The Prince and the Showgirl was his first and last attempt at directing a vehicle for a bona-fide American movie star. If Marilyn was ill-equipped to handle Olivier's rigid, stage-influenced directorial style, then Olivier was equally as inexperienced in interpreting popular material and handling screen idols.

The challenge of maintaining some semblance of a working relationship between Marilyn and Olivier fell on the shoulders of Milton Greene, while Arthur Miller assumed the duties of caretaker and manager for his unstable wife.

Miller was often placed in the awkward position of having to explain or defend Marilyn's behavior. Often, after several hours of waiting on the set, Olivier would have an assistant phone Miller every few minutes at the couple's rented estate in Eggham to inquire as to when the cast and crew could expect to see Marilyn that day.

Marilyn fell into a pattern of chronic insomnia, often becoming hysterical as the long nights wore on. Nightly vigils by her side became a common experience for Miller, who worked very little at his own craft during the four months of the film's production.

It was difficult for those living through the ordeal to have sympathy for Marilyn at the time, particularly after an episode in which she kept the elderly Dame Sybil Thorndike waiting on the set in full costume for hours.

Thorndike, ever the gracious professional, refused to criticize the obviously ill Marilyn. Thorndike insisted, "We need her desperately. She's the only one of us who really knows how to act in front of the camera."

After filming had been completed, Marilyn apologized to the entire cast and crew for her behavior.

The next several months would bring a string of disappointments for Marilyn, including an end to her partnership with Milton Greene and a miscarriage. Learn more in the next article in our series, Marilyn Monroe's Final Years.