Marilyn Monroe in 'Bus Stop'

Marilyn, in high spirits from her victory over Fox, returned to Hollywood in February 1956 to star in the film adaptation of William Inge's acclaimed play Bus Stop, a property Milton Greene had purchased exclusively for her.

Accompanied by coach Paula Strasberg and friend Amy Greene, Marilyn appeared more confident and serious than she had been when she last worked in Hollywood.

Advertisement

At a press conference to announce her career plans, Marilyn fielded questions with wit and grace. Perhaps recalling how the media had distorted her comments about The Brothers Karamazov, Marilyn requested clarification on many questions and parried reporters' attempts to catch her off-guard.

When one reporter hinted that her attire -- a dark suit with a high collar -- differed from her usual low-cut gowns and was perhaps meant to suggest a "new Marilyn," the actress neatly squashed the attempt to belittle her with the simple reply, "Well, I'm the same person. It's just a new suit."

Marilyn's performance in Bus Stop, her first since her training with Strasberg, remains the finest of her career. In this classic film adaptation, Marilyn plays a sweet, talentless saloon singer who calls herself Cherie.

Cherie hails from the Ozarks but is working her way across the Southwest toward Hollywood, where she hopes to be discovered and "get treated with a little respect, too."

At a rowdy cowboy bar in Arizona, she meets a naive young rancher named Bo, played by Broadway actor Don Murray in his film debut. Bo has traveled to Phoenix not only to participate in the big rodeo but also to find "an angel" -- that is, a wife to accompany him back to Montana.

Despite Cherie's checkered past, Bo sees her as his angel because she seems so fragile -- "so pale and white." He is determined to marry her, though she rejects his bullying tactics.

Only after his male pride is humbled and he apologizes for his domineering manner, does Cherie respond to him. Only after he shows respect for her feelings does she accept his proposal.

Marilyn immersed herself in the role eagerly. She was adamant about the details that would contribute to the realism of the character and promised to walk off the set if her demands weren't met. Her portrayal is vivid and affecting.

As a singer, Cherie is hopeless, completely unaware of her lack of talent and ignorant of the pitfalls that are sure to befall her if she pursues her ill-considered course to "stardom." A luckless girl who wants desperately to better herself, Cherie aspires to more than she will ever attain.

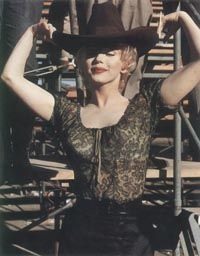

Though highly sexual, the character has little of the glamor that characterized Marilyn's other parts. Marilyn chose to portray Cherie as a ragged, cheaply costumed waif. She rejected the original costume designs and insisted on wearing tattered odds and ends she found in the costume department.

Milton Greene designed the pale, unflattering facial and body makeup that makes Cherie look tired and vaguely unhealthy. The singer's "hillbilly" accent, a key element of Marilyn's performance, was authentic and consistent.

Her training with the Strasbergs had paid off. Marilyn didn't just act the role of Cherie-on-screen, she became Cherie.

Upon hearing that Hollywood's most notorious blonde would star in Bus Stop, director Joshua Logan's initial reaction was, "Oh, no -- Marilyn Monroe can't bring off Bus Stop. She can't act." In a later interview, Logan ate his own words, lamenting, "I could gargle with salt and vinegar even now as I say that, because I found her to be one of the greatest talents of all time."

The mutual respect that existed between director and star was partially inspired by Logan's background. More active as a stage director than as a filmmaker, Logan was an acclaimed talent who had actually studied with Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theater. (He also knew the Strasbergs well enough to ask Paula not to interfere with his direction on the set.)

Like Marilyn, Logan was plagued by insomnia and exhaustion, so it is likely that he understood and was sympathetic to his star's personal problems. Though Marilyn's tardiness was not as evident during the production of this film, her new assertiveness often rubbed her costars the wrong way.

For instance, she did not get along well with her leading man, Don Murray. The relationship came to a boil during the shooting of a specific scene, when Cherie becomes angered at Bo and hits him with the train of her costume, which the clumsy cowboy has inadvertently pulled off.

In executing the action, Marilyn slapped Murray across the face with her sequin-studded costume with such force that blood was drawn. For reasons known only to herself and Murray, Marilyn refused to apologize.

Despite their differences during production, Murray has never harshly criticized Marilyn. "Marilyn Monroe had a childlike quality, and this was good and also bad," he recalled in a later interview.

"Director Joshua Logan wanted a two-head close-up for Bus Stop, one of the first in CinemaScope. She broke me up when, in one of the frames, the top of my head was missing. 'The audience won't miss the top of your head, Don,' she said. They know it's there because it's already been established.' But, like children, she thought the world revolved around her and her thoughts. She was oblivious to the needs of people near her, and her thoughtlessness, such as being late frequently, [was] the bad side of it."

Marilyn's performance in Bus Stop garnered some of the best reviews of her career. The well-respected Bosley Crowther of The New York Times opened his commentary on the film with: "Hold onto your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress in Bus Stop. She and the picture are swell."

Arthur Knight, noted film historian and critic, raved, ". . . in Bus Stop, Marilyn Monroe effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamor personality, a shapely body with tremulous lips and come-hither blue eyes."

Though the critics may have been ready to accept the rebellious star's lofty ambitions and absence from the screen, Hollywood was not. In turmoil and desperately trying to maintain control over its actors, the film industry exacted its revenge for Marilyn's defection by failing to nominate her for an Academy Award.

Critics had speculated in the trade papers that she would be nominated, and Logan, for one, felt she had been snubbed. He stated at the time, "[Marilyn's] performance that year was better than any other. It was a classical film performance." (The Best Actress Oscar for 1956 went to another Hollywood rebel, Ingrid Bergman, for her comeback role in Anastasia.)

In the next section, learn how Marilyn attempts to help Arthur Miller fight against Congress, which was accusing him of Communist leanings.