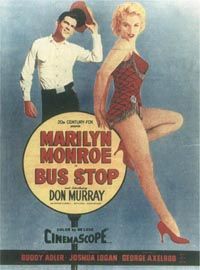

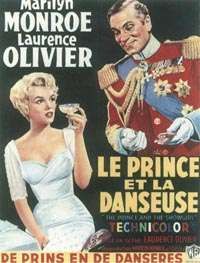

During the first part of her career, Marilyn Monroe rose from a bit player to a bona-fide movie star, even attaining her own star on Hollywood Boulevard following the success of her film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

How to Marry a Millionaire, Marilyn's next film, became the first comedy to be released in CinemaScope. If there was some trepidation that a comedy would not be able to make adequate use of the new widescreen process, then Twentieth Century-Fox hedged its bets by featuring three top blonde stars in the main roles.

Advertisement

Though supposedly based on a non-fiction best-seller by Doris Lilly, Fox executives discarded just about everything but the title and based the screenplay on a handful of plays that the studio owned.

Lauren Bacall and Betty Grable costarred with Marilyn in the film, with William Powell, Rory Calhoun, David Wayne, and Cameron Mitchell rounding out the male half of the cast.

How to Marry a Millionaire was directed by Jean Negulesco and scripted by the well-respected Nunnally Johnson.

Though several unkind remarks about Marilyn would later be attributed to Johnson, she got along quite well with Negulesco, who had a reputation in the industry as a woman's director.

During the production of the film, the artist-turned-director painted an oil portrait of his timid star and lent her several books, which he and Marilyn discussed at length.

However, in recountings of the production of this particular film, it is not how well Marilyn got along with her director that is best remembered but how well she got along with her female costars.

Just as the entertainment press had eagerly anticipated a feud between Marilyn and Jane Russell during Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, so they were hoping for some sparks to fly between Marilyn and Betty Grable on the set of Millionaire.

Considering the manner in which Marilyn's path had fatefully crossed Grable's during their careers, tension between the two stars would have come as no surprise.

Yet, Grable was unselfishly kind to Marilyn and harbored no resentment toward the new blonde on the Fox lot. Grable had defended Marilyn earlier that year over the controversy concerning her dress at the Photoplay awards, telling reporters that she was "a shot in the arm for Hollywood."

Later, in front of several people on the set, Grable reportedly told Marilyn, "Honey, I've had it. Go get yours. It's your turn now." Undoubtedly, Grable did feel she was being pushed aside, but she never blamed Marilyn. Instead, she directed her anger at Zanuck and Twentieth Century-Fox; on July 1, 1953, she stormed into Zanuck's office and tore up her contract.

Marilyn reciprocated Grable's kindness in small ways, despite the problems she often had coping with shyness and communicating with some of her peers. For instance, when Grable went home to care for one of her children who had become ill, Marilyn was the only person who called to inquire about the boy's condition.

After Grable left Fox, Marilyn inherited her dressing room, which was located in the Star Building on the Fox lot. Photographers wanted Marilyn to pose in front of the dressing room while Grable's name was still on it to suggest that Marilyn had succeeded her at Fox. She refused; she wanted no part of making Betty Grable feel as though she were finished.

Lauren Bacall found it more difficult to warm up to Marilyn than Grable had, perhaps because of Marilyn's continual tardiness on the set, her constant need for approval from Natasha Lytess, and her request for incessant retakes -- behavior Bacall considered unprofessional.

Marilyn's insecurities about her acting abilities and her sensitivity to the criticism of others made working in front of a movie camera much more difficult for her than modeling for a still camera had ever been. Her anxieties intensified as her roles became larger and her films more important, resulting in her need to bolster her confidence before appearing on the set.

Most often, her insecurities took several hours to overcome. She was consistently late to the set, which caused hard feelings because the rest of the cast had to wait for her, often for several hours.

Marilyn needed the approval of Lytess for each scene and looked directly at her at the end of each take; if Lytess shook her head disapprovingly, Marilyn requested a retake. The timid star tended to become more secure and give a better performance with each additional take, while her costars often lost their edge and spontaneity as the number of retakes increased.

But despite any hardships Marilyn put the cast through during the production of Millionaire, Bacall never spoke harshly of her costar.

The gracious actress later wrote in her autobiography: "A scene often went to 15 or more takes ... not easy, often irritating. And yet I didn't dislike Marilyn. She had no meanness in her -- no bitchery ... There was something sad about her -- wanting to reach out -- afraid to trust -- uncomfortable. She made no effort for others and yet she was nice."

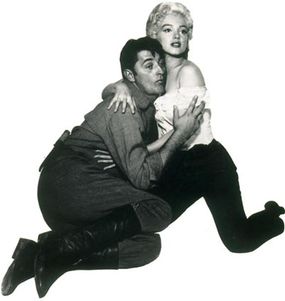

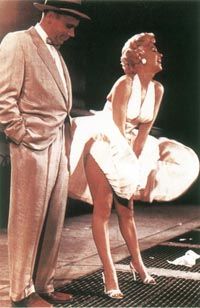

Marilyn's role in Millionaire showcased her talents as a comedienne, which many biographers and industry personnel have suggested was her true calling. As Pola Debevoise, Marilyn played a nearsighted department store model who never wears her glasses because, as Pola soberly notes, "Men aren't attentive to girls who wear glasses."

Pola's poor eyesight causes her to walk into walls, trip across the floor, and stumble on stairs. The sight of such a beautiful, voluptuous star as Marilyn Monroe blundering gracelessly into walls heightened the comic effect.

Marilyn's ability to perform physical stunts so adroitly was probably the result of her keen awareness of her body. She had always used her physical attributes to suggest aspects of her film characters; she had a knowledge and understanding of anatomy that other actresses did not possess.

She had studied human bone and muscle structure to help accentuate her physical presence, and coworkers have often testified how she practiced walking, gesturing, and even moving her facial muscles in front of a mirror.

Her work began to pay off in How to Many a Millionaire. Though generally regarded as lightweight fare, the picture was a critical and popular success. Marilyn was singled out in the majority of film reviews for her comic performance, though, once again, critics were reluctant to admit that she was truly talented.

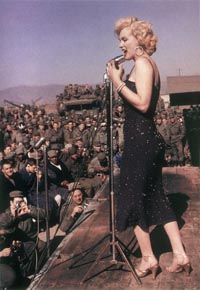

Shortly after the release of Millionaire, an unusual criticism of Marilyn appeared in East Germany's Berliner Illustrierte. A front-page article in the communist newspaper blamed the young star for many of the political ills plaguing America. The paper claimed that her function was to make the American people forget about the Korean War and the high cost of living.

The paper pontificated: "During the premiere of [How to Marry a Millionaire] in New York, fans literally tore her clothing from her body and hardly noticed that at the same time [Senator Joseph] McCarthy was violating the great democratic traditions of the American people."

The article is not only amusing in its dogmatic interpretation of Marilyn's impact on our country, but also indicates that her fame extended worldwide.

Next up: River of No Return. Learn about Marilyn's role in this film in the next section.