Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio

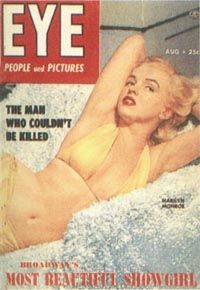

During the production of Niagara, the press began to compare Marilyn to Jean Harlow, the famous blonde sex symbol of the Depression era. After the film's release, the comparisons between Monroe and Harlow intensified.

Typical of this sort of commentary was an article by Erskine Johnson in the New York World Telegram & Sun titled "Marilyn Inherits Harlow's Mantle." Johnson wrote: "Hollywood took 14 years, three-score screen tests and a couple of million dollars to find a successor to Jean Harlow ... "

Advertisement

Aside from their platinum blonde hair, Jean Harlow and Marilyn Monroe did share some common characteristics. Both were able to project a healthy sexuality on the screen, without appearing vulgar or artificial. Publicity for both of the actresses emphasized their sexy glamor with such tantalizing tidbits as "she sleeps in the nude," or "she loves champagne."

Both had been married as teenagers before breaking into the film industry, and during the height of their celebrity, both were romantically linked with older, sophisticated men.

As Marilyn's popularity soared, the Harlow comparison faded, though the spectre of Jean Harlow haunted Marilyn in other ways. During the mid-1950s, columnist Sidney Skolsky, who had befriended Marilyn during her years as a starlet, wanted her to star in a biopic (biographical movie) of Harlow's life.

Though interested, Marilyn was disappointed in the sensationalism of the script offered her by Twentieth Century-Fox. After reading it, she prophetically told her agent and friends, "I hope they don't do that to me after I'm gone."

Skolsky continued to campaign for a Harlow biography starring Marilyn Monroe until the year Marilyn died. According to the columnist, "On the Sunday they found Marilyn dead, I had an appointment with her for that afternoon at four to work on The Jean Harlow Story." (A pair of mediocre Harlow biopics did finally appear in 1965, one starring Carol Lynley, the other featuring Carroll Baker.)

Aside from making her a full-fledged star who invited comparisons with a legend of Hollywood's past, Niagara was important to Marilyn on a more personal level as well.

During the shooting of the film in the summer of 1952, Joe DiMaggio began to seriously court Marilyn Monroe. Earlier that spring, a mutual acquaintance of Marilyn and Joe's had arranged for them to meet at DiMaggio's request.

The legendary ballplayer -- retired since 1951 -- had seen a publicity photograph of Marilyn with Chicago White Sox players Joe Dobson and Gus Zernial, and he had tracked her down from there.

Marilyn was reluctant to meet DiMaggio. She didn't follow baseball and was not attracted to sports figures. She expected DiMaggio to be wearing flashy clothes and to have slicked-back hair.

"I had thought I was going to meet a loud, sporty fellow," she said later. "Instead I found myself smiling at a reserved gentleman in a gray suit, with a gray tie and a sprinkle of gray in his hair. There were a few blue polka dots in his tie. If I hadn't been told he was some sort of ballplayer, I would have guessed he was either a steel magnate or a congressman."

Though DiMaggio had made a good first impression, Marilyn hesitated to go out with him again. She reportedly told the man who had introduced them, "He struck out."

The soft-spoken DiMaggio was smitten, however, and he phoned Marilyn repeatedly. His persistence eventually paid off, and despite their differences, the unlikely couple began dating.

Their relationship was fraught with problems almost from the beginning, mostly stemming from the public nature of Marilyn's career. A shy man, DiMaggio shunned publicity and the press, while Marilyn's career thrived on it.

DiMaggio disliked the hustle and limelight of Hollywood; Marilyn was inextricably caught up in it. DiMaggio protected Marilyn to some degree from the brutal side of Hollywood: the steel-hearted studio executives, the phony hangers-on, the snide remarks in the press about her acting abilities. He could not understand her devotion to such a distasteful business.

As a further annoyance, DiMaggio and Natasha Lytess had a mutual dislike and distrust for each other. Lytess thought Marilyn could do better than a former baseball player, while DiMaggio resented Lytess's control over Marilyn. As Marilyn and Joe grew closer, the relationship between the actress and her coach became less personal and more professional.

Complicating the issue was the change in Marilyn's star status from the time of the couple's initial meeting through their serious courtship. At the beginning of their romance, Marilyn was still appearing in minor or secondary roles at Fox. In the aftermath of the nude calendar story and throughout the production of Niagara, the publicity surrounding Hollywood's hottest starlet rapidly increased.

Marilyn began to participate in more and more promotional functions -- just the sort of events DiMaggio shunned. Bandleader Ray Anthony, for example, introduced a song called "Marilyn," written by Ervin Drake and Jimmy Shirl.

The song was presented to Marilyn by Mickey Rooney and Anthony at a party at Anthony's home. In true Hollywood style, Marilyn arrived at the poolside party in a helicopter. She was wearing the provocative red dress she had worn in Niagara.

More the impetus for a publicity stunt rather than an exciting, new pop song, "Marilyn" never made the top ten. With such lyrics as "No gal, I believe, beginning with Eve, could weave a fascination like my Ma-ri-lyn," the tune was doomed to novelty status.

A month later, Marilyn was the Grand Marshal for the parade for the 1952 Miss America pageant. During the festivities, she was asked to pose with several women from the armed services.

The low-cut summer dress she was wearing caught the attention of a photographer, who stood on a chair to better capture the outfit's full effect. Upon seeing the photo, an Army information officer ordered it killed because he did not want to give the parents of potential recruits the "wrong impression" about Army life. Information about the suppression of the photo was leaked to the press and then turned into frontpage news.

When asked her opinion of the situation for a story titled "Marilyn Wounded by Army Blushoff," Marilyn replied in her tongue-in-cheek manner, "I am very surprised and very hurt. I wasn't aware of any objectionable décolletage on my part. I'd noticed people looking at me all day, but I thought they were admiring my Grand Marshal's badge!"

The relentless emphasis by reporters and press agents on Marilyn's physical attributes became a sore point with DiMaggio as the romance progressed. Many assume that his quiet dignity and conservative demeanor made it difficult for him to accept any display or discussion of Marilyn's sexuality or famous figure.

It is possible that DiMaggio was just as angered by the press's condescending and often snide attitude toward Marilyn. As a popular, even beloved, celebrity himself, DiMaggio had had many personal encounters with the press and an adoring public. But the attention given him since the start of his own memorable career had been of a completely different nature than the attention paid to Marilyn.

In the end, DiMaggio's unhappiness with the press's treatment of Marilyn did nothing to alter the tone of the coverage. In fact, after the release of Niagara, the number of stories revolving around Marilyn's sexuality both on and off the screen steadily increased.

All this publicity did help Marilyn receive the film roles she was looking for. Next up: Gentleman Prefer Blondes.