Marilyn Monroe Develops Her Acting Talents

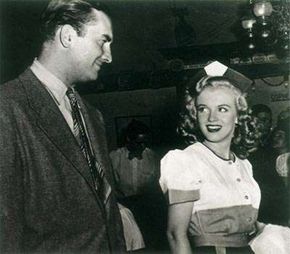

One day while walking across the Fox lot, Marilyn recognized an older man in a limousine as one of the studio executives. She smiled as he passed by, causing him to stop and chat with her. The man was Hollywood pioneer Joseph Schenck, then nearly 70 years old and an executive producer at Fox.

Schenck, who began in the film industry about 1912, founded 20th Century in 1933 and became chairman two years later when his company merged with Fox Films. A stint in jail on charges involving union payoffs forced him to resign his position in 1941, but Schenck came back as an executive producer a short time later.

Advertisement

He took an immediate liking to Marilyn that afternoon and invited her to his home for a dinner party the following week. The unknown starlet became a regular at Schenck's small, intimate dinner parties, and the two grew quite close.

Allegations that Marilyn was his mistress and used that position to further her career remain unverifiable, even dubious. Given Schenck's advanced age and the fact that Marilyn's career floundered for several more years after their meeting, it is unlikely that the relationship was more than that of a grand old man of Hollywood advising a beautiful protégée in the ways of "the business."

Marilyn was not the only starlet who attended his dinner parties, and her presence at such functions was probably calculated by Schenck to impress and innocently amuse his colleagues.

Schenck remained Marilyn's friend and sometimes mentor for several years, until she made a conscious effort to remove herself from the Hollywood scene during the mid-1950s. Schenck died in 1961, just a year earlier than Marilyn. Confined to bed near the end of his life, the elderly mogul was delighted when Marilyn came to visit him for what would be the last time.

On the way home, according to Marilyn's friend and publicist Rupert Allan, she cried openly. Marilyn's respect for Schenck's power and position went beyond the level of what he could do for her career.

She talked of sitting at his feet for hours and listening to his stories about Hollywood. "He was full of wisdom like some great explorer," she recalled. "I also liked to look at his face. It was as much the face of a town as of a man. The whole history of Hollywood was in it."

In August of 1947, Marilyn was assigned a role in the drama Dangerous Years, a film exploiting America's rising concern over postwar juvenile delinquency. Her role as a waitress in a local teen hangout was small but slightly more substantial than her part in Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!. This time she was given a close-up, which is important in establishing or reinforcing an actor's image. She received fourteenth billing in a film that credited 15 actors.

Though Dangerous Years would seem to have been a logical step in Marilyn's fledgling career, Fox did not renew her contract when it expired a few days after her shots had been completed. This would not be the last time that Marilyn got caught up in the turnover of contract players at option time.

Though the reasons behind Fox's decision to drop her option are not known, the studio exhibited little interest in developing her acting career at this juncture. Fox had seemed content simply to feature her in dozens of cheesecake publicity photos or to shuttle her around to publicity events, such as the Fox Studio Club golf tournament. Marilyn proved adept at publicity functions, particularly if there were photos involved, but she seriously desired to be an actress.

The major star at Fox during this era was another blonde actress, Betty Grable, whose popularity had soared during World War II because of her famous pinup photos. Marilyn, too, had an extensive background in modeling for pinups, but Grable also had a great deal of experience in show business.

By the time she was Marilyn's age, Grable had already toured in vaudeville, appeared on the stage, and performed on radio, giving her a confidence and style that Marilyn lacked. Marilyn's lack of show-business experience may have prevented the studio from grooming her to follow in Grable's footsteps -- a role the studio did assign to singer-dancer June Haver.

Out of work and out of luck, Marilyn responded to a general casting call advertised in the Los Angeles Times for a play at the Bliss-Hayden Miniature Theatre in Beverly Hills. Marilyn landed the second lead in the play, a lighthearted spoof of Hollywood entitled Glamour Preferred.

The Bliss-Hayden, which no longer exists, had been established in the 1930s by stage performers Harry Hayden and Lela Bliss. The theater was best known as a showcase for the talents of young movie hopefuls, who needed to catch the attention of important agents or studio talent scouts.

Students or performers from the Bliss-Hayden who went on to careers in the movies included Veronica Lake, Doris Day, Debbie Reynolds, Craig Stevens, and Jon Hall. Los Angeles theatergoers who regularly attended the Bliss-Hayden in the fall of 1947 through the summer of 1948 were fortunate enough to witness a young Marilyn Monroe perform in her only extensive attempt at public stagework.

Though Glamour Preferred ran for just three weeks in October and November of 1947, Marilyn appeared in at least one other play at the small theater. According to Don Hayden -- son of Harry Hayden and Lela Bliss -- Marilyn costarred in a production of Stage Door in the late summer of 1948.

In a 1975 interview, Lela Bliss recalled Marilyn's experiences at the Bliss-Hayden: "She could have played anything. We never had any struggle about parts with her -- she was always happy to play what you cast her in."

While still under contract to Fox, Marilyn had begun taking acting lessons at the Actors Lab, a practice she continued after she was dropped by the studio. She paid for her lessons with occasional modeling jobs, though the Lab allowed her some leeway in paying her bill.

The Actors Lab, operated by Roman Bohnen, J. Edward Bromberg, and Morris Carnovsky, was considered a West Coast offshoot of the Group Theatre of New York. By most accounts, Marilyn was a quiet and shy student while at the Lab; any influence that her two years of studies there may have had on her acting ability was probably slight.

Like the Group Theatre, the Lab was left of center in its political orientation, and some have suggested that Lab members may have influenced Marilyn's thinking. Never an overtly political person, Marilyn nonetheless always considered herself a part of the working class and remained unfazed by the Lab's leftist politics.

In the early 1950s, after Marilyn had left the Actors Lab, Carnovsky and his wife were labeled Communists by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), an official committee of the U.S. House of Representatives assigned to investigate allegedly un-American organizations, particularly those suspected of Communist affiliations.

HUAC would descend on Hollywood with a vengeance in the early 1950s. The result was extensive blacklists of actors and other industry personnel suspected of Communist leanings; a fear gripped Hollywood in which no actor or actress wanted to be remotely associated with leftist groups.

At that time, a studio executive visiting the set of All About Eve noticed Marilyn reading The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens. Steffens was a famous journalist who had made his name by exposing the corrupt practices of government and business. The executive considered it "dangerous to be reading such radical books in public," but Marilyn continued to read the book anyway.

In the end, Marilyn suffered no consequences as the result of her association with the Actors Lab, probably because her burgeoning image as a sex symbol completely overshadowed any other aspects of her personality. Throughout her life, and to no detriment to her career, she would foster friendships with intellectuals associated with the political left.

Find out about Marilyn Monroe's days with Columbia Pictures in the next section.