To the audience, the most important aspect of digital cinema is the projection system. This is the final piece of technology that controls how the movie actually looks at the end of the line.

Pretty much everybody agrees that a good film projector loaded with a pristine film print produces a fantastic, vibrant picture. The problem is, every time you play the movie, the film quality drops a little. When you go to a movie that's been playing for a few weeks, you'll probably see hundreds of scratches and bits of dirt.

Many critics hold that a projected digital movie is inferior to a pristine film print, but they recognize that while a film print gradually degrades, a digital movie looks the same every time you show it. Think of a CD as compared to an audio tape. Every time you play an audio tape, the sound gets a little warped. A CD's digital information sounds exactly the same every time you listen to it (unless it gets scratched).

Today, there are two major digital cinema projector technologies: Micromirror projectors and LCD projectors.

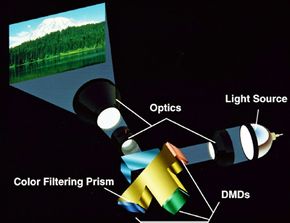

Micromirror projectors, like Texas Instruments' Digital Light Processing (DLP) line, form images with an array of microscopic mirrors. In this system, a high-power lamp shines light through a prism. The prism splits the light into the component colors red, green and blue. Each color beam hits a different Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) -- a semiconductor chip that is covered in more than a million hinged mirrors.

Based on the information encoded in the video signal, the DMD turns over the tiny mirrors to reflect the colored light. Collectively, the tiny dots of reflected light form a monochromatic image. To see how this works, imagine a crowd of people on the ground at night, each holding a square-foot mirror. A helicopter flies overhead and shines a light down on the crowd. Depending on which people held their mirrors up, you would see a different reflected image. If everybody worked together, they could spell out words or form images. If you had more than a million people, pressed shoulder to shoulder, you could make highly detailed pictures.

In actuality, most of the individual mirrors are flipped from "on" (reflecting light) to "off" (not reflecting light) and back again thousands of times per second. A mirror that is flipped on a greater proportion of the time will reflect more light and so will form a brighter pixel than a mirror that is not flipped on for as long. This is how the DMD creates a gradation between light and dark. The mirrors that are flipping rapidly from on to off create varying shades of gray (or varying shades of red, green and blue, in this case).

Each micromirror chip reflects the monochromatic image back to the prism, which recombines the colors. The red, green and blue rejoin to form a full color image, which is projected on the screen.

LCD projectors, such as JVC's Digital Image Light Amplifier (D-ILA) line, work on a slightly different system. These projectors reflect high-intensity light off of a stationary mirror covered with a liquid crystal display (LCD). Based on the digital signal, the projector directs some of the liquid crystals to let reflected light through and others to block it. In this way, the LCD modifies the high-intensity light beam to create an image.

There is a flip-side to digital projector technology. In both projector designs, individual pixels may break from time to time. When this happens, it degrades the image quality of every single movie shown on that projector. In contrast, if a film print gets scratched, it's only that particular movie that's damaged -- the next print looks fine.