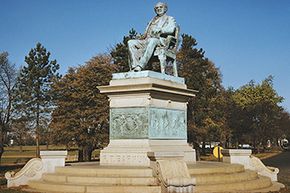

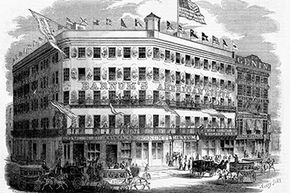

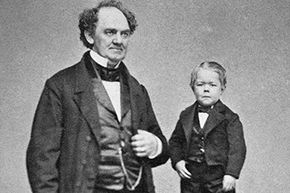

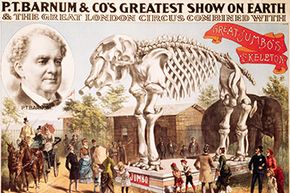

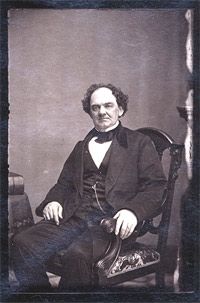

If you want to understand the origins of American showmanship, look no further than P.T. Barnum. He was the single most influential public figure in American entertainment during the latter half of the 19th century. His legacy still resonates today, from his wildly successful promotion tactics to the introduction of the first three-ring circus. His exhibitions and tours of the "Feejee Mermaid," Tom Thumb and singer Jenny Lind caused a sensation among the American public.

Barnum's life story is as astounding as one of his shows and sometimes as hard to believe as his ridiculous exhibitions. His was a true story of rags to riches — and then to rags and riches again. He yearned for stability but never stopped taking risks. He yearned for respectability but never hesitated to manipulate his audiences or to appeal to a base human interest in the grotesque.

Advertisement

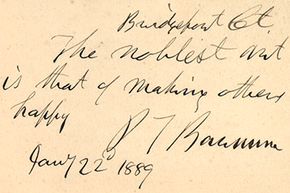

He legitimized his profession, saying, "The noblest art is that of making people happy." But he also had a mercenary spirit, having been quoted as saying, "every crowd has a silver lining" [source: Ringling]. He preached that people should live within their means, but he sank into debt on multiple occasions.

Barnum became a champion of the temperance movement — after drinking heavily during a romp in Europe. He was an abolitionist and an ardent Unionist during the Civil War — after owning a slave and using her as an exhibition. He preached that we shouldn't care what our neighbors think of us, yet he was so concerned about how he would be remembered that he requested (and was granted) the publication of his obituary before his death.

Was Barnum a hypocrite? Did he have a good heart under his shrewd business tactics? Let's examine his life, and you can decide for yourself how genuine Barnum was. Step right in and take a gander at the greatest showman the world has ever seen!

Advertisement