Some people think of sword swallowing as a magic trick. After all, as with most magic tricks, sword swallowing doesn't seem like something that should be possible. It can be a little easier to accept the idea that it's all an illusion than to believe that a person can guide a long piece of metal all the way into his or her gut. If you've ever watched a sword-swallowing performance, you may have also gotten the impression that the performer is trying to gain the audience's trust, just like a magician does. He might invite members of the audience to join him on stage to inspect the swords — or even pull them from his mouth.

Several sources support the idea that there's a trick to sword swallowing. Famed magician and escape artist Harry Houdini wrote about sword swallowing in "The Miracle Mongers, an Expose." According to Houdini, some of the sword swallowers of his time swallowed metal sheaths before their performances [source: The Miracle Mongers]. Encyclopedia Britannica online reiterates this idea. It defines sword swallowing as a magic trick and claims that most performers prepare for the event by swallowing guiding tubes about 17 to 19 inches (45 to 50 centimeters) long and about an inch (25 millimeters) wide. [source: Encyclopedia Britannica].

Advertisement

There is a trick to real sword swallowing, but it doesn't involve illusions or preemptively-swallowed metal tubes. Instead, it involves lots of physical and psychological preparation. For some performers, learning to swallow a sword can take years.

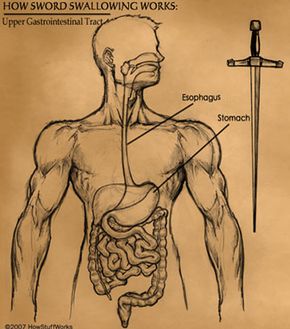

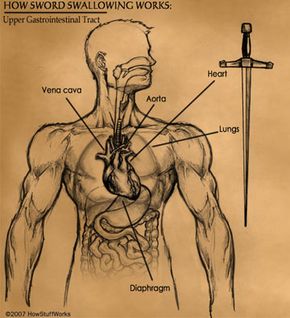

The act of swallowing a sword is an interaction between two fundamentally dissimilar objects — a human being's upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract and a sword. The upper GI tract is a series of connected, living organs. It includes the throat, the esophagus and the stomach. The GI tract is relatively soft, and it has several pronounced curves in its relaxed state. A sword, on the other hand, is inanimate and rigid. Although some sword swallowers can swallow a wavy blade, like a kris, and some incorporate curved swords into their performances, most swallowed swords are completely straight.

You can think of the GI tract as a living scabbard that the sword slides into. However, barring ineptitude, sheathing a sword in an ordinary scabbard does not generally have the potential to be fatal — sword swallowing does. Although the swords used in sword swallowing do not have sharp edges, they are still capable of puncturing, scraping or otherwise perforating the GI tract. If someone swallows multiple swords, the blades can slide past each other like scissors. When this happens, the inner surface of the GI tract can get caught between the moving swords, leading to serious lacerations.

In addition, it's easy to fit a sword into a matching sheath, but learning how to swallow a sword takes a lot of practice. We'll look at exactly what happens, as well as how swallowing a sword is different from swallowing food, in the next section.

Advertisement