Michelangelo's Pieta and David

The timing of Michelangelo's arrival in Rome in 1496 was fortunate because it coincided with the exhibition of newly unearthed sculptures and ruins of antiquity. The classical sculptures, nude and Herculean in proportion, celebrated the ideals of moral virtue, physical beauty, and truth.

The discovery of these pieces represented a crucial bridge from the Gothic works of the Middle Ages to the inspired sculpture and painting of the early Renaissance. Their grandeur would prove prophetic of the most majestic aspects of Michelangelo's future creations.

Advertisement

The young Florentine thrived in this environment, absorbing the classical subject matter and exploring the relationship between science, art, philosophy, and humanity -- theories he had been introduced to under the guidance of Lorenzo de' Medici.

In 1498, while in Rome, Michelangelo accepted the most important artistic commission of the era, the Pietà for St. Peter's Basilica. The French cardinal Jean de Willies de la Grossly commissioned the work for his tomb in St. Peter's. According to the formal agreement, the Pietà was to be "the most beautiful work of marble in Rome, one that no living artist could better."

The lamentation of Christ was a theme popular in Northern European art since the fourteenth century, and it traditionally focused on the portrayal of pain through the two figures of Mary and Jesus. But Michelangelo's interpretation of Mary holding a dead Christ in her arms is remarkable in its devotion to the Renaissance Humanist ideals of physical perfection and beauty. Michelangelo boldly celebrated the intimacy and majesty of a single moment frozen in time, choosing to portray Mary as a chaste and glowing young woman holding the gracefully lifeless body of the Savior across her lap.

Innovative in technique as well as content, Michelangelo worked the piece in the round, using a drill for speed and achieving a highly polished sheen that made it fairly impossible to believe the sumptuously sculpted figures began as a block of cold stone.

Even at the early age of twenty-three, the Michelangelo's understanding of the composition of the piece, the unique triangular shape that conveys a stunning grandeur, and human anatomy served him well in his creation. The Pietà is widely held as his finest work, and it marked a watershed event of the Italian High Renaissance.

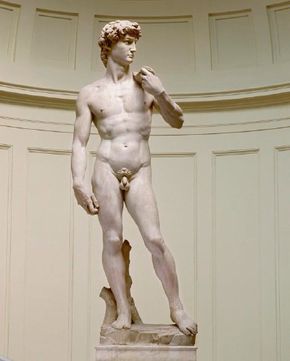

As Michelangelo worked on the Pietà in public during the Holy Year celebrations of 1500, large crowds gathered to watch him. His fame spread throughout Europe. Building on the confidence gained from this early success, Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1501 to share in the celebration of the newly formed Florentine Republic and was commissioned by the powerful Wool Guild to create a statue of David for the city. A fierce patriot and a loyal supporter of the new government, Michelangelo seized the opportunity to express his religious faith and political views in a monument of gigantic scale. In doing so, the artist again dared to break with traditional forms and themes.

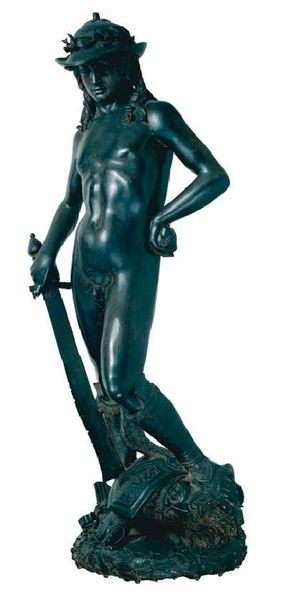

Donatello was the first of the great Florentine sculptors, indeed the most important Renaissance sculptor prior to Michelangelo, and his David (1430s) may be the earliest known freestanding nude statue since antiquity. Though Michelangelo once studied under Donatello's former assistant, Bartholdi DI Giovanni, the young artist's style transcended Donatello's. There is a striking contrast between Donatello's soft and effeminate nude and Michelangelo's powerfully expressive model of heroic courage.

Of still greater contrast is the 1470s David by Andrea Del Verruca. Though possessing a quiet dignity that reminds us of Michelangelo's, this bronze sculpture shows a pensive, elegant lad, fully clothed and gentle in victory. Michelangelo's groundbreaking treatment of the subject resulted in a colossal sculpture, an athletic and passionate youth, gloriously nude and powerfully poised to defend his city. The statue served as an embodiment of Michelangelo's identification with the Old Testament figure and an acknowledgment of his self-appointed role as champion of the new Florentine Republic.

After creating these masterpieces, Michelangelo acquired a new patron -- Pope Julius II. Learn more about this relationship and the art it produced in the next section of this article.