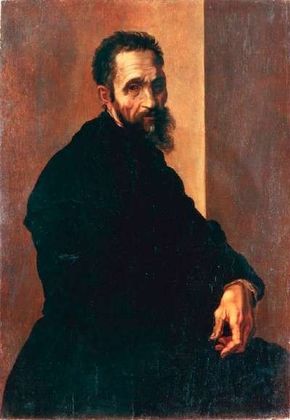

Born on Sunday, March 6, 1475, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni spent his early years in the Italian village of Caprese, a child destined to be shaped by the men in his life. His mother, Francesca Neri, inattentive and in failing health, entrusted the care of Michelangelo to the wife of a stonecutter in a town near Florence. From that moment, history has no account of her further involvement in Michelangelo's childhood or later life. His father, Lodovico, was a podestà, a minor Florentine official of noble lineage, who was consumed with keeping what little remained of the family money and properties.

Michelangelo endured a childhood lacking in affection. His mother died when he was only six years old, and Michelangelo's father, recognizing the boy's intellectual potential, enrolled him in the school of master linguist Francesco Galeota to prepare young Michelangelo for a career in business. It was here, as he studied Latin, that Michelangelo met a student of painter Domenico Ghirlandaio and decided to follow his artistic desires by agreeing to apprentice in the painter's workshop.

Advertisement

This life-altering decision, made by a shy and ill-tempered thirteen-year-old Michelangelo, shocked and infuriated his father, who had hoped that his son would become a respected merchant and preserve the family's tenuous position in Florentine society. In the early days of the Italian Renaissance, there was a stigma associated with the practice of art because it entailed manual labor.

Michelangelo's decision to defy his father and risk his family's social standing created a distance between the two men that would haunt the artist throughout his life. Within this conflict is found an understanding of Michelangelo the artist and, more importantly, the man. Despite his intellectual and artistic accomplishments, Michelangelo led a life punctuated by intense conflict.

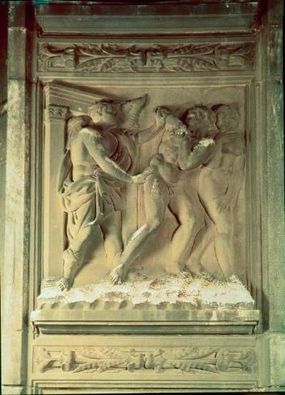

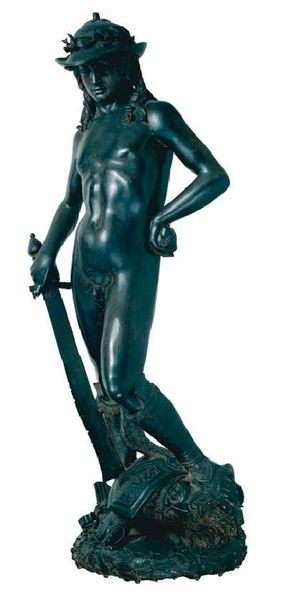

Soon after joining Ghirlandaio to learn the art of fresco painting, Michelangelo left his apprenticeship to study sculpture and anatomy at the school in the Medici gardens. His early success there won him an invitation to the home of Lorenzo de' Medici, the Magnificent, and, more importantly, exposed him to noted humanists, scientists, and poets who were regulars at the Medici court. Though their radical beliefs were often at odds with the artist's strong religious faith, these men of the Renaissance, among them poet Angelo Poliziano and humanist Marsilio Ficino, intrigued the young Michelangelo. Their impact is apparent even in his earliest works.

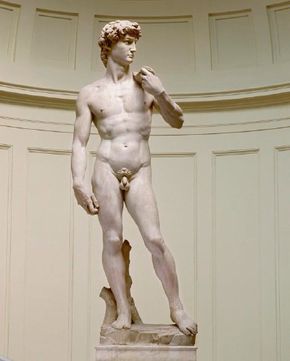

Michelangelo felt an almost religious calling to sculpt, to unveil the spiritual significance of physical beauty. The artist believed that this was the primary manner in which God shared his grace with humanity. But his theology was not pure, and as the temptations of science and politics whispered in his creative ear, Michelangelo struggled to reconcile these influences by giving each a powerfully balanced voice in his creations.

In his personal diary, Michelangelo reflected on his first two sculptures, each a small bas-relief, noting, "Already at 16, my mind was a battlefield: my love of pagan beauty, the male nude, at war with my religious faith. A polarity of themes and forms...one spiritual, the other earthly, I've kept these carvings on the walls of my studio to this very day."

The lifelong battles with powerful patrons, the heartbreak of artistic dreams unrealized, and the anguish of failed relationships that plagued Michelangelo's personal and professional life and fueled his seven decades of artistic genius can be traced to the underlying theme of conflict that haunted the artist until his dying day.

A fierce patriot and champion of the Florentine Republic, Michelangelo was repeatedly forced to align himself against the Medici family and their dynastic ambitions for Florence in spite of their early and important patronage of his career.

Learn more about Michelangelo's struggles in the next section of this article.