Since the dawn of the moving picture in the late 1800s, filmmakers have been experimenting with ways to make films more exciting. Film pioneer Georges Méliès used all sorts of camera trickery to create short films like his 1898 "Un Homme de Tête," where the character played by Méliès repeatedly removed his head and put each head on a table, or his 1902 "Le Voyage Dans la Lune" where he sent men to the pie-faced moon on a rocket shaped like a bullet.

Some artists turned to animation to create fanciful stories and situations on film. Fully animated cartoons have been around since 1908, when comic strip artist Émile Cohl drew and filmed hundreds of simple hand drawings to make the short film "Fantasmagorie." Others followed suit, including Winsor McCay with "Gertie the Dinosaur" in 1914, which involved thousands of frames and was longer and more smooth and realistic than most cartoons of the day. Most tended to be a bit rough and jerky.

Advertisement

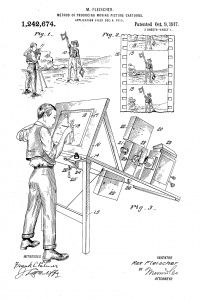

Right along with the drive to create new, fantastical effects to amaze and entertain, there has been a parallel and seemingly (but not really) paradoxical pursuit of realism to make films more believable. Some creators strive to increase the level of realism in cartoons, as well. One bit of technology for animating life-like motion is rotoscoping, and it was developed almost exactly 100 years ago.

Rotoscoping requires relatively simple, although time-consuming, steps and equipment. At its most basic, it is taking film footage of live actors or other objects in motion and tracing over it frame by frame to create an animation. However, rotoscoping can also be used to execute composited special effects in live-action movies.

In some circles, rotoscoping of cartoons has a bad reputation as a cheat distinct from "real" animation drawn from scratch, and computer generated artistry has taken the place of a lot of the more old-school methods. But rotoscoping is still a potentially useful tool in the arsenal of the animator or filmmaker.

Advertisement