Blam! Zap! Pow! These are more than page-bound sound effects; they're emblems of a unique form of human communication. They're a hallmark of -- you guessed it -- comic books.

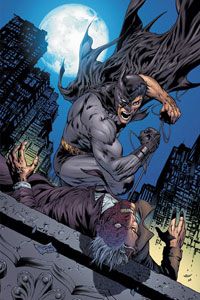

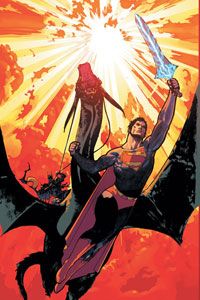

Comic books have a storied place in the history of human publishing and strong roots in American culture. In many ways, they're the apple pie and Fourth of July versions of American literature, full of iconic imagery, action, drama and, sometimes, even MOMA-worthy artistry.

Advertisement

Comic books and their artistic cousins saturate our society. You'll find comic strips and comic books at newsstands everywhere, and graphic novels and comics in strip mall bookstores and geek boutiques all across the land. Comic-based movies now routinely show up in theaters and draw huge crowds. It's not a surprise that these flicks are popular: Comic books have inspired a fanatical subculture, one that features its own lingo, slang and inside jokes, as any fan of Kevin Smith's films can attest.

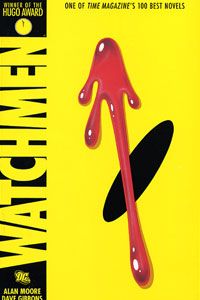

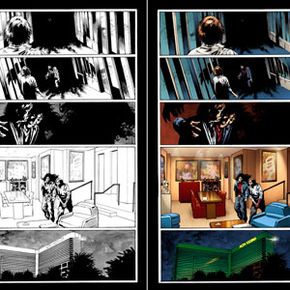

Films aren't the only medium that pulls material from comics. In fact, there are so many varieties of comic books and related types of work that it's worth reviewing the term. A comic book blends drawn art -- color, black-and-white or both -- with text to tell a story. Comic books are usually 20 to 30 pages long; once they get longer, they're sometimes called graphic novels.

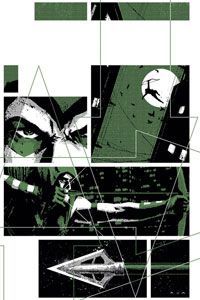

Stylistically, comic books are pretty easy to spot. Each page of the books is segmented into panels (or frames), which have borders that separate them from other panels. Individual panels contain one part of a story (perhaps dialogue between characters), or a character's inner thoughts (represented by speech and thought balloons) that leads into the next panel. Panels are routinely separated by blank areas called gutters. Artists lay out each page so that panels logically flow to one another, guiding the reader's eyes so that he or she absorbs the story in a sequential manner. It's for this reason that comic books are often called sequential art -- a type of graphic storytelling.

It's not uncommon for people to scoff at anyone who uses the word "art" in describing comics. Comics have a long history that's been linked to low-brow, cheap entertainment. But comics these days aren't just longer versions of the Sunday funnies. They span as many genres and subjects, both frivolous and mature, as traditional novels.

Comics are a global phenomenon, but for the purposes of this article, we'll focus mostly on the American evolution of comic art, with nods to notable international examples. Keep reading, and you'll see how comic books first came to life, how they're more popular than ever, and how their creators keep finding new audiences to enthrall.

Advertisement