Marilyn Monroe achieved great fame for her movies, and seemed to have found happiness with her third husband, playwright Arthur Miller. But Marilyn's unpleasant behavior and her increasing dependency on Arthur Miller to see her through each day strained their marriage considerably. The strain was magnified by Marilyn's discovery of Miller's personal notebook, an event that has been recounted so many times that its true impact on Marilyn is difficult to fully grasp.

In the notebook, Miller had recorded some unflattering personal thoughts about Marilyn and his relationship with her. According to some accounts, his written comments revealed his disappointment in Marilyn's behavior during the production of The Prince and the Showgirl; in other accounts, he had compared Marilyn to his ex-wife.

Advertisement

The story was embellished over time and through many retellings, even by Marilyn herself; one version claims that Miller's personal notes referred to his new bride as a "whore."

Whatever the exact nature of Miller's jottings, some of Marilyn's closest friends, including the Strasbergs, maintained that her discovery was a heartbreaking one that signaled the beginning of the end of her marriage. Miller himself has always denied that this episode had any dire effect on the relationship.

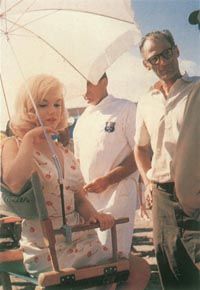

Marilyn Monroe Image Gallery

Despite Marilyn's personal and professional conflicts during production, The Prince and the Showgirl has become one of the actress's most acclaimed films.

Well-crafted and beautifully photographed by Jack Cardiff, the movie tells the story of a turn-of-the-century American showgirl who has a brief encounter with the stuffy Grand Duke Charles, Prince Regent of Carpathia. During the course of their evening together, the unassuming Chorine reunites the Prince with his estranged son, teaching the royal Romeo about mutual respect and fairness.

The improbable teaming of Marilyn Monroe and Laurence Olivier does nothing but enhance this sophisticated comedy. The innocence and sincerity of Marilyn's character, Elsie Marina, perfectly complements the pompousness of Olivier's Prince Regent.

Marilyn's image, with its combination of innocence and sexuality, is once again used to splendid advantage. While Elsie's sexy exterior initially attracts the Prince to the Showgirl, her inner goodness and native wisdom transform him into a fair-minded father and more democratic leader.

Just as Cherie in Bus Stop bore similarities to the woman who portrayed her, so did Elsie Marina recall the real-life Marilyn -- but in a far less tragic way.

Whereas Cherie was searching for respect, just as Marilyn would for most of her career, Elsie's resemblance to the actress was tongue-in-cheek. Like Marilyn, Elsie is never on time, not even to meet her royal date; and, like Marilyn, Elsie is repeatedly described as childlike.

Also, just as Marilyn's strap had broken at the press conference with Olivier, Elsie's dress strap breaks in the presence of the Prince. In real life, Marilyn's insecurities and bad habits caused delays and frustration; on the screen, these same qualities were presented as endearing.

The fusion of Marilyn Monroe with the characters she played was something that Marilyn personally detested, but in The Prince and the Showgirl and Bus Stop, it may have helped her fans accept the less gracious aspects of her real-life personality -- many of which were reported and exaggerated in the press.

Marilyn's involvement in The Prince and the Showgirl earned her worldwide attention. Before the film was completed, she was asked to attend a Royal Command Film Performance before Queen Elizabeth. Along with several other film stars, Marilyn was presented to the Queen, who complimented the famous actress on her curtsy.

After the film was released to much acclaim, particularly in Europe, Marilyn won Italy's David di Donatello Prize for Best Foreign Actress of 1958, as well as France's Crystal Star Award for Best Foreign Actress.

Both awards are considered the equivalent of the Oscar, but Marilyn's chance for the real thing was denied her, as she was once again passed over by Hollywood at Academy Award-nomination time.

Upon their return to the States, Marilyn and Miller retreated to the privacy of a rented cottage in Amagansett, Long Island. Miller completed a few short stories, including "Please Don't Kill Anything," inspired by Marilyn's inability to tolerate suffering in any living creature, and "The Misfits."

Marilyn enjoyed some peaceful days and restful nights at Amagansett, though she still suffered frequent bouts of insomnia. After the stressful experiences in London, the newlyweds were determined to focus on their life together.

Away from the pressures of her career and the fear that few in the film industry respected her, Marilyn was heard to say, "Movies are my business, but Arthur is my life."

A handful of disappointing episodes interrupted the couple's secluded existence. In May 1957, Miller's contempt of Congress trial ended. Marilyn told newsmen she was confident her husband would win his case, but Miller was convicted on two counts of contempt. He received a 30-day suspended sentence and a $500 fine.

Though the penalty was hardly devastating, Miller had fought hard to be acquitted as a matter of principle. He chose to appeal the conviction, which was finally overturned in August 1958.

The spring of 1957 brought another milestone,

as Marilyn severed her personal and business relations with partner Milton Greene. Their friendship had lost much of its initial closeness after her marriage to Miller, while their business association rapidly deteriorated during the production of The Prince and the Showgirl.

During the group's stay in London, Greene had attempted to organize a British subsidiary of Marilyn Monroe Productions, an act that Miller interpreted as conducting business behind Marilyn's back.

In addition, Marilyn resented Greene's congenial relationship with Olivier, and she suspected him of shipping antiques back to the States and billing the charges through Marilyn Monroe Productions.

After returning to New York, communication between the two partners disintegrated completely. Marilyn had trusted Greene in such an idealistic manner that any deal he attempted for his personal benefit -- though perfectly legitimate -- was considered by her to be a betrayal.

Marilyn, with the help of Miller and his lawyers, decided to break with Greene and sue him for control of Marilyn Monroe Productions. Greene eventually settled the matter by accepting a mere $ 100,000 for his share of the company.

Whatever the reasons behind the dissolution of the Greene-Monroe partnership, the ambitious photographer cannot be faulted for the work he did on Marilyn's behalf. Both Bus Stop and The Prince and the Showgirl -- properties Greene personally selected for Marilyn -- were finished within their budgets, and both films were considered critical and popular successes.

The most devastating blow to Marilyn's emotional and mental state occurred during the summer of 1957. Marilyn had become pregnant in June, a stroke of good fortune that left her ecstatic.

She adored children and had always been active in children's charities. She was devoted to Miller's two children by his former marriage and remained close to DiMaggio's son until her death.

Miller once observed, "To understand Marilyn best, you have to see her around children. They love her; her whole approach to life has their kind of simplicity and directness."

Sadly, she could not carry her own baby to full term. A few weeks into her pregnancy, she was in such physical agony that Miller called an ambulance to rush her to Doctor's Hospital in New York. Doctors discovered that her pregnancy was tubular, and were forced to surgically terminate it.

In the weeks following her loss, Marilyn grew increasingly despondent. In an effort to bolster her spirits, Miller discussed his plans for turning "The Misfits" into a suitable dramatic script for her.

He planned to focus on the female character Roslyn, who is mentioned only in the dialogue of the short story, and make her a central part of the action for the film. Marilyn was pleased by the idea but could not fully shake her depression. Her dependency on medication to sleep -- and perhaps escape -- increased significantly.

At least once during this period she sought oblivion by swallowing too much medication, though whether she did so as a destructive act or as an attempt to sleep through her anguish can only be surmised. Marilyn's spirits remained depressed, and she would make no public appearances until the end of January 1958.

While in England, Miller had sold his beloved Connecticut residence. When a 300-acre farm near his previous Roxbury home went on the market, Miller wasted no time in purchasing it.

The reserved, serious-minded writer loved the quiet life of the country, though Marilyn often longed for the stimulation of New York. The couple divided their time between the solitude of their country farm and Marilyn's new apartment in the city. Miller maintained studies at both residences, where he continued to work on his script adaptation of "The Misfits."

After almost two years, Marilyn gets back to movie making with the film Some Like It Hot. Learn more about her role in this movie on the next page.

Advertisement