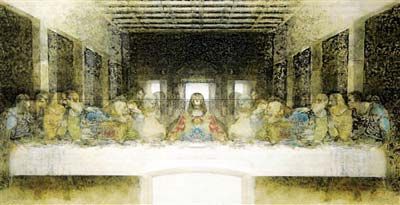

It wasn't until the 14th century that perspective showed up in art. An Italian architect named Filippo Brunellesco who served as an architect stumbled upon perspective as he oversaw construction of the Baptistery in San Giovanni. Following Brunellesco's discovery, linear perspective -- a technique that uses a single point as the focus -- became all the rage in art. In linear perspective, all lines in a painting go to a common point (think about railroad tracks that vanish in the distance), and it creates the impression of depth and distance [source: Dartmouth].

Until artists discovered perspective, they relied on height and width to give their works dimension. So paintings seemed flat. Early artists could only make objects smaller or larger to create the appearance of distance. Early Egyptian paintings are a good example of lack of perspective.

Artists also use light and shadow to create the illusion of depth. Light demonstrates a surface's closeness to the light source. It protrudes and therefore reflects more light. On the other hand, a shadow denotes an area that is closed off, or farther away, from the light source. If you put light and shadow together, you have the illusion of depth -- or length, the third dimension.

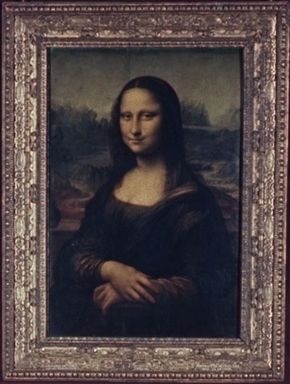

Modern artists have a command of linear perspective, and they use the interplay of light and shadow to create paintings that look almost as if they're alive. But it's impossible to get past the fact that the medium in which a painter works exists in only two dimensions. Ultimately all depth created through perspective and light and shadow is a trick, an optical illusion, and this illusion gives rise to other illusions -- including eyes in a painting following you.

So how does it work? Essentially, what is going on is that the light, shadow and perspective depicted in a painting are fixed, meaning they don't shift. Remember when your friend stared forward and you walked from side to side? His or her eyes didn't follow you because the light and shadow, as well as perspective you see, actually change. Features that were close to you as you stood on one side are farther away when you stand on the other side. Since the elements of perspective and light and shadow are fixed in a painting and don't change, they look pretty much the same no matter from what angle you look at it [source: Guardian].

So if a person is painted to look at you, he or she will continue to look as you move about the room. If a person is painted looking away from you, the light, shadow and perspective shouldn't allow him or her to ever look at you, even if you move yourself to the point where the person has been painted looking toward.

In the 19th century, a man named Jules de la Gournerie first had the idea that the phenomenon could be proven using math. He came close, but it wasn't until 2004 that a group of researchers proved the idea. Using an image of a mannequin's torso, the team employed a computer to map out dots of the points on the torso which appeared close and far away. The researchers did this from different angles, including 90 degrees (looking straight at the image).

When they compared the dots, they found that features which appeared far away and close from one angle also appeared that way from other angles, too [source: Ohio State University]. In other words, the locations of the dots prove that perspective doesn't change much when it's fixed in a painting or photo. Of course, this doesn't apply to paintings in haunted mansions -- the eyes in those paintings really do follow you.