Graboid Evolution and Biology

We've all heard tales of the legendary graboid, but some accounts are older than others. The native Shoshone people tell of a great aquatic serpent that, eons ago, burrowed out into the land and remains there to this day [source: Parker]. The myth actually meshes nicely with the theory that graboids date back some 400 million years in the fossil record to the Devonian Period.

Devonian Nevada was a rich environment of river deltas and estuaries, dominated by fish, invertebrates and early amphibians. Back then, an aquatic graboid ancestor may have enjoyed a steady diet of delicious, prehistoric morsels -- but disaster necessitates change.

Advertisement

Starting roughly 374 million years ago, a series of Late Devonian extinction events (possibly caused by severe carbon dioxide depletion) wiped out 70 percent of all invertebrate species [source: Smithsonian Institution]. In time, the landscape transformed into the desolate Nevadan landscape we know today -- but the graboid survived.

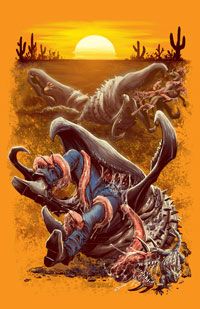

Modern graboids are massive, reaching lengths of up to 30 feet (9.1 meters) and weights topping 20 tons (18 metric tons). Physically, they resemble massive grubs. Rigid spikes cover the creature's bloated body and, much like the bristly setae on earthworms, these protuberances both sense the creature's immediate surroundings and vibrate to pull it through the ground. The graboid's head is a tough, chitinous beak with both a lower jaw and two hooked mandibles. The creature also boasts a cluster of three tentacle-like appendages in its throat, all of which terminate in prehensile "mouths" capable of grabbing prey and pulling them down the monster's throat.

Completely blind, the creatures depend on sound to hunt prey. They focus their attacks on the epicenters of surface noise and occasionally give chase with surprising speed for such large organisms. Still, for all their ferociousness, graboids are severely limited in habitat, native only to desert regions of loose soil. Human structures such as concrete aqueducts further limit this endangered species, creating lethal barriers to their high-speed movements.

As an apex invertebrate predator, the graboid's place in the fossil record is questionable, Generally speaking, the softer and rarer the creature, the less likely it is to wind up preserved in stone. In 2009, geologist Dr. Kevin Page claimed to have found fossil evidence of a 160-million-year-old species of sand worm in Devon, England, but this beastie measured only 3 feet (0.9 meters) in length [source: Laing].