Parts of the Club

Any golf club has three basic parts:

- The grip - the part you hold

- The shaft - the part that connects the grip to the head

- The head - the part that actually hits the ball

If you walk down the golf club aisle of a large sporting goods store, you'll see a variety of designs for all three of these parts, but you'll also notice that all clubs have certain similarities. That's because every golf club used in a round of golf that's either part of a tournament or that might count toward a golfer's handicap must conform to rules established by one of two organizations. In the United States, the rules of golf, including golf club regulations, are established by the United States Golf Association (USGA). The rules of golf for the rest of the world are established by The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of Saint Andrews (in Scotland). For the most part, the rules established by the two bodies are the same, though there are some differences. Now let's look at the main parts of the club.

Advertisement

The Grip

The grip of the golf club is important because it connects the club to the golfer's hands. According to the rules of golf, recognized by both ruling bodies, the grip has to be round, without obvious bumps, lumps or hollows. You'll see grips made of rubber or leather with an assortment of small holes, grooves or ridges. All of these qualities are designed to make it easier for the golfer to hold onto the club without making the grip so large that it will run afoul of the rules. There are various sizes of grips to accommodate different hand sizes and grip styles. According to most experts, the ideal material and design of the grip are a matter of personal preference.

The Shaft

The shaft of the golf club connects the grip to the head and, like the grip, must be basically round in cross section. Most modern golf club shafts are made of either steel or a carbon-fiber and resin composite. Carbon fiber has the advantage of being lighter than steel, but clubs with carbon-fiber shafts also tend to be more expensive. In addition, some golfers say that hitting a golf ball with a carbon-fiber club feels different than hitting the ball with a steel-shafted club. This difference arises because steel and carbon fiber transmit vibrations differently. As in grips, shaft material tends to be a personal preference.

The stiffness of the shaft is another variable. Most manufacturers rate their shafts in one of six degrees of stiffness. From least to most stiff they are:

- L - Ladies

- A - Seniors

- R - Regular

- F - Firm

- X - Extra Firm

- S - Stiff

As you can see, there isn't a grade for "wobbly" or "limp." Most golfers, at least in the United States, seem to prefer a shaft that is stiffer, and manufacturers have obliged. But if golfers prefer stiffness to limpness, why not make everything super-stiff? The answer has to do with distance and strength.

If you're Tiger Woods, or if you swing a golf club as he does, your body will coil and uncoil during a golf swing so that you apply plenty of energy to the face of the golf club when it meets the ball. If your swing is this good and if you are this strong, you want a very stiff shaft so that every bit of energy you generate in your swing is delivered to the ball, and none is absorbed in making the shaft of the club bend and vibrate.

If, on the other hand, you do not have a Tiger Woods swing, then you can get a shaft with some flexibility to do some of the work of sheer muscle with a well-timed "whip" motion that stores energy from the top of the swing in a bent shaft, then releases it in time to deliver that energy to the ball. How much flex might you need for your particular swing? If you're serious about answering this question, then you should have a golf pro (a club professional who's a member of the PGA of America) analyze your swing and make a recommendation.

The Head

The head of the golf club is where all the energy of the swing is transferred to the golf ball. There is more variation in the appearance of golf club heads than there is in either shafts or grips, but all the variations fall into one of three broad categories: the heads of woods, irons and putters.

Woods

Woods have the largest heads of any golf club. These large clubs are designed to send the ball 300 yards or more with a single swing. What is it about the bulbous shape of the wood that suits it for these long-distance strikes? The answer has to do with the wood's shaft, especially in the largest wood, called the driver. Wood shafts are considerably longer than the shafts of most other clubs. This length increases the power that can be transferred to the ball, but it also makes it less likely that the ball will meet the the quarter-sized sweet spot in the middle of the club face. When an off-center hit occurs, the head of the club tends to twist, pointing the face in an unintended direction, and sending the ball the wrong way.

A golf club designer has to balance a number of factors. A heavy club head best resists twisting and so suffers the least from a less-than-perfect swing. On the other hand, a golfer can generally swing a club with a lighter head at a greater speed, which generates more energy to be transferred to the ball and so sends the ball a greater distance. Over the past 100 or so years, golf club designers have attempted to strike a balance between light and heavy clubs. The large head of a driver and the combination of metals like steel, titanium and bronze that go into various drivers, are attempts to balance stability and light weight. The driver head shape allows designers to move the weight in the head to points that enhance stability (points that are different for each brand of club, and provide one of the differences touted by manufacturers when claiming superiority for their clubs). The driver head shape also allows the head to glide over grass and ground rather than digging into the turf.

Irons

Irons are designed for a greater variety of shots than woods. Where woods tend to be optimal for long to very long shots, the shots made using irons range from 200 yards or more, in the case of 2 irons, down to 40 yards or less in the case of the various wedges. Club designers must cope with the same issues in irons as in woods, but their shorter shafts and the less exaggerated swings with which they are used have led to different solutions for different types of players.

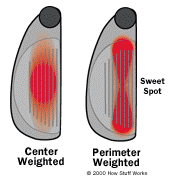

Only 25 years ago, most companies' irons were very similar -- a blade-shaped head with most of the weight concentrated low and in the center of the club. This design gave an additional emphasis to shots in which the ball was hit with the club's sweet spot. The heads of these clubs were steel, and usually shaped by forging -- hammering hot metal under great pressure. When a golfer hit the ball off-center, there was very little in the club's design to prevent it from twisting and delivering a disappointing shot.

In the last 25 years, designers have developed clubs that have approximately the same weight as the older clubs but have it distributed around the perimeter of the club, so that the head is far more resistant to off-center twisting and therefore far more forgiving of golf swings that are off line by a few millimeters. In addition, modern metal alloys have allowed for larger iron heads, which increases the size of the "sweet spot," thereby increasing the possibility of good results with a less-than-perfect swing.

If you look in the golf bag of a PGA Tour player, you'll probably see the same sort of forged blade-style irons you would have seen 25 years ago. That's because their concentration of weight behind the sweet spot make the most of a professional's very consistent, very accurate swing. Recreational golfers, on the other hand, have embraced the perimeter-weighted iron for the good results they get even with less consistent swings.

Putters

Putters have a relatively simple job: to strike the golf ball with a face perpendicular to the path of a gentle swing and cause the ball to roll along the ground until it falls into a hole. Twisting is still a concern with off-center hits, but a putter is designed to transfer far less energy to the ball than either irons or woods. It's interesting, then, to note the incredible array of shapes taken by the heads of putters -- blocks, blades, short, long, thick, thin, etc., and the various patterns of lines found on the faces. So why is there such variation in a club designed for such a simple task? Because the mechanical simplicity of putting places most of the pressure on the golfer's mental processes, where there is room for far more variation than in any golf swing.