For baseball fans, civil rights activists and anyone who has seen the movie "42," it's considered common knowledge that Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball's color barrier when he took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Robinson's emergence in the big leagues is hailed as a pioneering moment, not only in the integration of professional sports, but in the struggle for racial equality in America at large. Often overlooked in the story of Robinson's crowning achievement, however, are all the nonwhite players who had already been playing on baseball's biggest stage before he landed in Brooklyn.

Advertisement

Robinson made history April 15, 1947, when he started at first base (he later spent most of his career patrolling second base) in a home game at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, an event widely regarded as the moment when baseball's color barrier was officially shattered. While there was no written rule in place banning Black players from suiting up for professional clubs, big league owners had operated under an unwritten agreement to keep African Americans off their teams since 1889 [sources: Corcoran, Dreier].

As a four-sport athlete at UCLA who thrived in the Negro Leagues before taking up with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson turned heads all the time for his athletic abilities. But he also tried to challenge segregation. In 1944, Robinson was court-martialed after refusing to move to the back of an Army bus in Fort Hood, Texas, where he was stationed as a second lieutenant. He was later acquitted on charges of insubordination and honorably discharged.

Robinson's arrival in Brooklyn was largely orchestrated by Branch Rickey, the legendary Dodgers president who had previously built a dynasty with the Cardinals in St. Louis and who is also credited with creating the minor league "farm" system that big league teams use to develop talent to this day.

But Rickey and Robinson were not alone in their effort to desegregate the national pastime. Many other people had been agitating for this in the years prior to 1947.

Long before Robinson crossed the color line, sports journalists, reporters for African American newspapers, union leaders and civil rights activists had demanded that it be obliterated, a campaign that mirrored similar struggles to fight discrimination in housing, employment and the military. Throughout the 1930s and '40s, unions and civil rights groups picketed places like Yankee Stadium and Ebbets Field in New York and Wrigley Field in Chicago, demanding baseball integrate. These protests set the stage for Robinson to join Major League Baseball (MLB).

Robinson found his launching pad to big league superstardom in the Negro Leagues, where he and a number of top African American ballplayers displayed their talents while shunned from MLB. He wasn't the only MLB-caliber player who toiled there: Catcher Roy Campanella and legendary pitcher Satchel Paige were among a number of Negro Leaguers to later join Robinson in the majors.

Rickey tapped Robinson to cross the color line, not only because of his athletic prowess, but also because of Robinson's relatively young age (28), college education and experience competing with and against white players. Rickey also valued Robinson's temperament, in particular his agreement not to lash out against the taunts, threats or other offensive behavior he would inevitably face over the course of that first full season [source: Dreier].

Rickey's motivation was not just a singular desire to right a wrong. The crafty executive thought that integration could help sell tickets by attracting Black fans, a growing number of whom were moving to larger cities. "Jackie's nimble, Jackie's quick, Jackie makes the turnstiles click," is how one historian described the thinking at the time.

The move worked. Despite meeting with intense racism and antagonism along the way — Robinson led the National League in number of times being hit by a pitch in his rookie season — he went on to enjoy a Hall of Fame career. He led the Dodgers to six National League pennants over 10 seasons with the club, collecting the first Rookie of the Year award, an MVP award and a batting title along the way.

In 1997, MLB retired Robinson's No. 42 for all teams, meaning that no baseball player can take a pro ball field with that number on his back. However, since 2004, MLB has honored April 15 as Jackie Robinson Day and all players wear No. 42 on their jerseys on that day to play. There are also a number of educational activities to commemorate the day.

There is no doubt that Jackie Robinson is the best-known color barrier crosser in baseball history, but he was not the first.

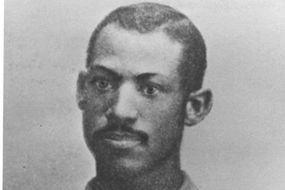

Before Jackie Robinson, there was Moses Fleetwood Walker. A catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings, Walker became the first African American player in the big leagues in 1884 when the team joined the American Association, the precursor to today's American League.

The college-educated Walker seemingly happened upon baseball history: He was already playing for Toledo when the American Association absorbed the team and others from what was then the minors-level Northwestern League. Walker had helped Toledo win the Northwestern League championship

Walker's majors run was short-lived. He suffered an injury after appearing in 42 games and was still trying to work his way back through the minor leagues five years later when Black players were effectively banned from the game's highest level. Up to this time, the American Association and National League had competed with a third major league, the Union Association, and Walker's presence in Toledo was permitted based on a lack of available talent. That all changed when the Union Association folded in 1889 and owners in the two other leagues tacitly agreed to keep Black players out [sources: Regan, JockBio].

Although the color line remained in place, a number of nonwhite players were able to cross or at least step around it based on racial ambiguity. Albert "Chief" Bender, a half Chippewa pitcher from Minnesota, pitched his first game in the majors in 1903 for the Philadelphia Athletics. Bender went on to win three World Series titles over 14 big league seasons, including an impressive 23-win campaign in 1910, and is a member of baseball's Hall of Fame [source: Warrington].

In addition, some 50 lighter-skinned Latino players took the field for various Major League ball clubs before Robinson made his debut in 1947. Among them were a number of Cuban athletes, including Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans, who suited up for the Cincinnati Reds in 1911, and flame-throwing pitcher Adolfo Luque, who won World Series championships with the Reds in 1919 and the New York Giants in 1933 [sources: Inskeep, Bjarkman].

Nor was Robinson the only African American player in the MLB ranks during his first season in Brooklyn. Larry Doby debuted with the American League's Cleveland Indians in the middle of 1947, but played second fiddle to Robinson, likely because he played in only 29 games and collected only five hits while Robinson was leading the Dodgers to a World Series.

Despite the efforts of nonwhite players who came before him, Robinson is rightly hailed as breaking baseball's color line. He was the first unambiguously Black player to appear for a big league team in at least 60 years. Robinson's arrival in Brooklyn was the culmination of a wide-ranging struggle for integration in the baseball arena and an important step forward for the American civil rights movement. It also opened the door to an influx of nonwhite talent that included Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente and Juan Marichal.

Advertisement