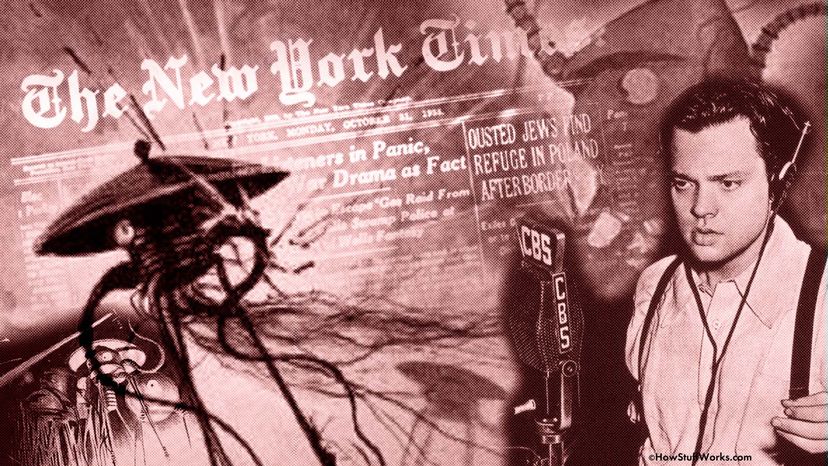

Before his ascent to cinematic genius, Orson Welles was just a fledgling director in New Deal America. But in 1938, the man who later brought the world "Citizen Kane" caused quite a stir when his pre-Halloween radio drama struck terror in the hearts of Americans nationwide, who believed that what they heard was real.

At the time, Welles, who was just 23, was the director of a New York City-based program called "Mercury Theatre on the Air." It was a radio show featuring a renowned New York drama company founded by Welles and John Houseman (best known for his role in "The Paper Chase"). But it's most remembered for that infamous night of Oct. 30, 1938, when Welles and the troupe updated H.G. Wells' 19th-century science fiction novel "War of the Worlds" for the national radio program's Halloween episode.

Advertisement

Before the era of Netflix and chill, families sat in front of their radios and listened to music, the news, plays and other shows for enjoyment. In 1938, Sunday evenings were one of the most popular times for radio programming. But Welles was competing for an audience with the prime time ratings winner, a show called the "Chase and Sanborn Hour," starring ventriloquist Edgar Bergen, which also aired at 8 p.m.

That's why Welles got the idea to adapt "War of the Worlds" from Victorian England to present day New England — in hopes of reviving the story and gaining new listeners.

Advertisement