By the time colonial marines arrived on LV-426, xenomorphs had killed or cocooned most of the colonists and multiplied into a full hive society.

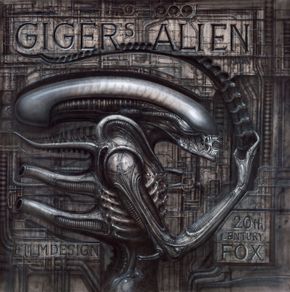

These xenomorphs were anatomically distinct from their Nostromo counterpart, despite originating from the same cache of eggs and having gestated inside human hosts. These differences might be due to genetic variation, rapid adaptation to LV-426 surface conditions (rather than the environment aboard the Nostromo), differing age or differing caste.

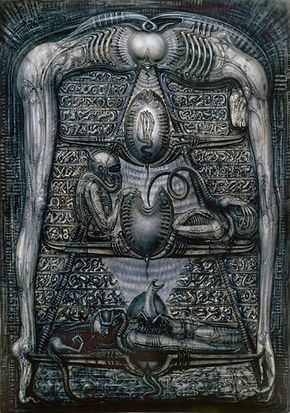

The caste theory is especially interesting, given that the LV-426 xenomorphs displayed eusocial organization. They boasted a hive society with a central queen -- a lone, reproducing female analogous to those of ants, bees, termites and mole rats here on Earth.

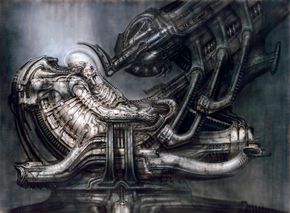

The queen herself differed dramatically from the rest of the hive. More than twice the size of a typical xenomorph, she also boasted a longer tail, an armored cranial crest and an extra set of arms.

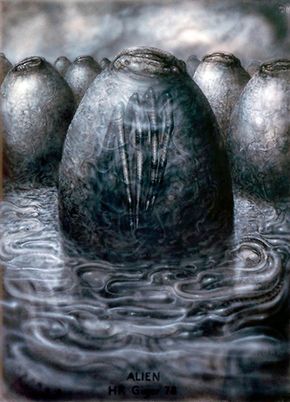

Most notably of all, the queen developed an enormous distended abdomen (not unlike that of a termite queen) and ovipositor with which to deposit fully formed eggs. Anchored in place by secreted resin, the queen's abdomen rendered her immobile -- though she later proved capable of shedding this portion of her body when threatened.

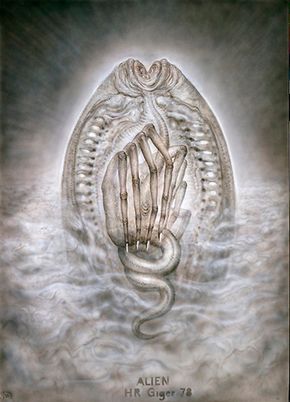

How do xenomorph populations produce a queen? Dubious accounts speak of a royal facehugger, which carries the queen embryo -- though this explanation raises as many questions as it answers. For a more likely answer, let's look at how terrestrial creatures produce a queen.

In the termite world, winged reproductive male and female termites called alates fly away from a thriving termite mound. The female lands, sheds her wings and mates with a king. Then the royal couple digs its way into the ground to start a new mound, where she'll lay one egg every 3 seconds for the next 15 years [source: Nelson and Silva]. Honeybees create a new queen by feeding larvae a diet of royal jelly, which worker bees secrete. Female naked mole rats simply fight it out to see who is worthy to breed.

With the xenomorph, we're forced to dismiss gender-based theories. All xenomorphs are essentially female -- though it might be more accurate to view them as asexual or hermaphroditic. At any rate, there are no documented xenomorph kings to parallel termites or mating drones to parallel honeybees.

Amazonian ants on Earth actually provide a useful comparison, having gradually abandoned sexual reproduction and become an all-female species that breeds through asexual cloning [source: Gill]. As a downside, the Amazonian ants suffer from reduced genetic diversity, leaving whole populations vulnerable to parasites or disease. The xenomorph, however, seemingly obtains genetic diversity through the parasitic impregnation of host species -- making the existence of males unnecessary.

In the end, the origin of xenomorph queens remains a mystery, but this much seems reliable: While a single xenomorph is capable of propagating its species through the cocooning of a host, larger populations produce a queen in order to ensure mass production of eggs. Their means of queen production may lie in violent completion, specialized diet, hormonal triggers or something utterly incomparable to terrestrial modes of life.