Mechanical Royalties

Record companies and recording artists, as well as the writers and publishers, all make money based on the sale of recordings of their songs. How those royalties are calculated, however, is about as intricate and controversial as everything else in the music industry.

Writer/publisher mechanical royalties

First, there is the calculation of mechanical royalties for writers and publishers. These royalties are paid by the record company to the publisher. The publisher then pays the writer a share of the royalty (typically split 50/50).

Advertisement

In the United States, the royalties are based on a "statutory rate" set by the U.S. Congress. This rate is increased to follow changes in the economy, usually based on the Consumer Price Index. Currently, the statutory rate is $.08 for songs five minutes or less in length or $.0155 per minute for songs that are over five minutes long. So, for example, a song that is eight minutes long would earn $.124 for each recording sold.

As in most areas in the business world, however, there is room for negotiation. It is not uncommon -- in fact, it is more the norm -- for record companies to negotiate a deal to pay only 75% of the statutory rate, particularly when the writer is also the recording artist. (See the "Controlled Composition Clause" below.) Although there is a statutory rate, there is no law against negotiating a deal for a lower one. Sometimes it is in the best interest of all parties to agree to a lower rate.

Recording-artist mechanical royalties

Recording-artist royalties (and contracts) are extremely complex and a hotbed of debate in the music world. From the outside, the calculation appears fairly simple. Artists are paid royalties usually somewhere between 8% and 25% of the suggested retail price of the recording. Exactly where it falls depends on the clout of the artist (a brand new artist might receive less than a well-known artist). From this percentage, a 25% deduction for packaging is taken out (even though packaging rarely costs 25% of the total price of the CD or cassette).

That sounds simple enough, but there are many more issues that affect what a recording artist actually makes in royalties.

- Free goods - Recording artists only earn royalties on the actual number of recordings sold -- not those that are given away free as promotions. Rather than discounting the price to distributors, many record companies give a certain number away for free (about 5% to 10% depending on the artist). Recording companies also give away many copies to radio stations as "promo" copies. There is also a reduction in royalties made for copies of the recording sold through record clubs.

- Return privilege - Recordings in the form of CDs or cassettes have a 100% return privilege. This means that record stores don't have to worry about being stuck with records they can't sell. Most other businesses don't work this way, but the music industry has to be more flexible and timed to demand. What's hot today may be forgotten tomorrow... This leads us to reserves. The recording company may hold back a portion of the artist's royalties for reserves that are returned from record stores. (Usually about 35% is held back.)

- 90% - Back in the days of vinyl records, there was a lot of breakage when record albums were shipped out for distribution. Because of this, recording companies only paid artists based on 90% of the shipment, assuming that 10% would be broken. Even as vinyl was phased out, this practice continued. Today it is gone for the most part, but there are still a few holdouts.

So, here is how it looks so far. Let's say a CD sells for $15. Right away we deduct 25% from that for packaging, which makes the royalty base $11.25. Now let's say our artist has a 10% royalty rate and that his CD sells one million copies. That sounds great! The artist would earn $1,125,000! Except 10% of those were actually freebies, so we really have to calculate that royalty based on 900,000, which makes the royalty $1,012,500, and of course, there are few costs we haven't talked about yet.

Advances and recoupment

Typically, when recording artists sign a recording contract or record a song (or album), the record company pays them an advance that must be paid back out of their royalties. This is called recoupment. In addition to paying back their advance, however, recording artists are usually required under their contract to pay for many other expenses. These recoupable expenses usually include recording costs, promotional and marketing costs, tour costs and music video production costs, as well as other expenses. The record company is making the upfront investment and taking the risk, but the artist eventually ends up paying for most of the costs. While all of this can be negotiated up front, it tends to be the norm that the artists pay for the bulk of expenses out of their royalties.

Let's see what these recoupable expenses do to our artist's $1,012,500 royalty we calculated earlier. Suppose the recording costs were $300,000 (100% recoupable), promotion costs were $200,000 (100% recoupable), tour costs were $200,000 (50% recoupable), and a music video cost $400,000 (50% recoupable). That comes out to:

$300,000 + $200,000 + $100,000 + $200,000 = $800,000

Suddenly our artist isn't making a million plus, he's making $212,500. But don't forget there is also a manager to be paid (usually 20%), as well as a producer and possibly several band members. The artist won't see any royalty money until all of these expenses are paid.

Controlled-composition clause

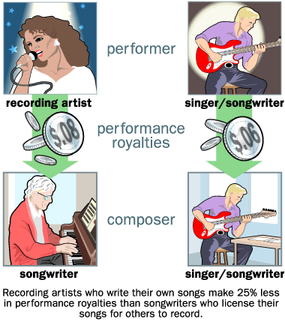

So far, it sounds like the money isn't in making the music, it's in writing it. While this is a true statement, controlled-composition clauses make it less fair to folks who are both the songwriter and recording artist of a song.

A controlled composition is a song that has been written and/or is owned by the recording artist. Because mechanical royalties paid to songwriters and publishers are not recoupable by the record company, meaning the record company can't deduct any expenses from them, record companies usually negotiate into the singer/songwriter's contract that the mechanical royalty rate he will receive as the songwriter/publisher will be 75% of the usual amount. In other words, as the writer of a song you record yourself, you get 25% less royalty money than you would get for writing a song that someone else records. But you'll get performance royalties when the song is played on the radio, TV, etc.

Internet royalties

With the explosion of the Internet and the ease of downloading music onto your computer, a whole new royalty arena has opened up in recent years. Record companies usually treat downloads as "new media/technology," which means they can reduce the royalty by 20% to 50%. This means that rather than paying artists a 10% royalty on recording sales, they can pay them a 5% to 8% rate when their song is downloaded from the Internet. In the case of downloaded music, although there is no packaging expense, many record company contracts still state that the 25% packaging fee will be deducted.

An alternative to this royalty payment method also exists for Internet music sales. While it is most often used by Internet record labels, it may still catch on as recording artists begin to push harder for it in their contracts. This other method creates an equal split of the net dollars made on music downloads between the record label and the artist. This net figure is arrived at after the costs have been deducted, including costs of the sale, digital rights management costs, bandwidth fees, transaction fees, mechanical royalties to songwriters/publishers, marketing costs, etc.