Before today's spandex-clad (and some sequined) Olympians strived for the gold, silver or bronze, the inventors of the Olympic Games, the sixth-century Greeks, competed for victory -- and olive oil.

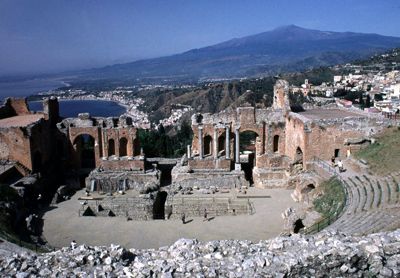

These men weren't the kind of live-breathe-and-eat the sport athletes that convene at the Olympics today. They were ordinary tradesmen in the ancient Greek world -- a mass of land that stretched from the Black Sea to Spain. Every four years, they trekked to Olympia to gain honor, political clout and social status through athletic victory.

Advertisement

These games were certainly about winning, but that wasn't their primary purpose. They were founded to build diplomacy across the Greek world and to honor the greatest of the Greek gods: Zeus.

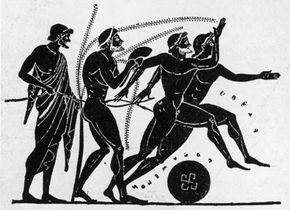

While the first official games were held in 776 B.C.E., their origins stretch even further back. According to one myth, the very first games occurred during a battle between Zeus and Cronus, when the two gods fought for control as chief of the gods (Zeus won). Some time later, a demigod named Herakles held a festival of athletic events to honor Zeus for granting him military victory over the city-state of Elis.

What's the reason for these legends? Well, there's not a whole lot of information about the first Olympics. What we know about them comes from a few archaeological relics and the accounts of ancient travelers like Pausanias and the treatises of some early thinkers, such as Herodotus and Pliny.

Dicey as the details may be, the picture we have of the earliest Olympics reminds us of the games' real meaning. A fragmented world needed something to unify it, and a little healthy competition was just the thing. Not that these games were perfect -- there were scandals, sabotage and plenty of over-greased, over-confident men in the ancient stadiums. What were the stakes? Who stood to gain the ultimate victory, and whose bitter losses turned them into the laughingstocks of their city-states? And what caused some spectators to be thrown to their deaths off mountain-tops?

Advertisement