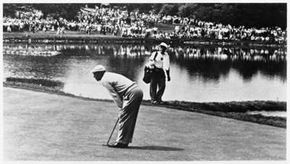

Ben Hogan's career in golf was a saga of overcoming, one that is legendary in its proportions.

Best Golfers Image Gallery

Advertisement

Hogan grew up in difficult financial circumstances, and more significantly had to live with the calamity of his father's suicide.

A basic swing flaw took him years to overcome. When he found the solution, he lost more time serving in the armed forces.

Then, Hogan barely survived a devastating highway accident from which he suffered physical pain the rest of his life. But Hogan persevered to become one of golf's all-time great champions, not to mention one of the game's most intriguing personalities.

William Ben Hogan was born in 1912 in Stephenville, Texas, and was raised in nearby Dublin until the age of 10, when his father Chester took his own life. Following that tragic event, Ben's mother moved the family (Ben and his older sister and brother) to Fort Worth, where Ben, at age 12, learned of golf as a caddie and found his lifework.

As a teenager, Hogan clearly had enough innate ability to consider a future as a golfer, but it did not come easily. Extremely private, he did not socialize well, which kept him from the networking that helps start careers and move them forward.

Also, being small of stature, Hogan developed an extended golf swing in order to create power. He achieved the power but at the expense of accuracy. Hogan's driving, in particular, featured a wild hook that for the first eight years of his professional career (he turned pro at age 18) kept him on the periphery of the tournament circuit.

Hogan concluded in subsequent years that the most important shot on any golf hole is the first one, the drive, and he eventually became exceptionally accurate off the tee while retaining sufficient power. What's more, he added to that a stunningly precise approach-shot game that made up for a lifetime of relatively ordinary putting skills.

Hogan often said he figured out the golf swing by himself -- "dug it out of the dirt," as he liked to put it. He took the idea of practice to an extraordinary level for golfers of his era.

While this surely was an important element in his success, he was also an inquisitive student of the golf swing who picked up ideas on technique from many sources, one of which was Henry Picard, a Masters and PGA champion in the 1930s who would become one of golf's best teachers.

Picard convinced Hogan that to beat his hook, he had to "weaken" his left-hand grip by turning the hand more to the left. Seemingly overnight, Hogan's basic shot became a left-to-right power fade, a trajectory that came to be known as the "Hogan Fade." The flight pattern would influence how the game would be played from then on.

In early 1940, Picard's lesson hit home. Hogan won his first professional tournament individually, the much prized North and South Open. (In 1938, he had shared victory with partner Vic Ghezzi in the Hershey Four-Ball.)

The next week, Hogan won the Greater Greensboro Open, and later in this "coming out" season he won twice more. After nine years of struggle, during which he more than once had to leave the tournament circuit for lack of funds, Hogan was at last fulfilling his promise.

From 1940-42, he won 15 tournaments, and in each year he was the Tour's leading money winner. All that was missing on his increasingly impressive résumé was a major title.

Hogan was primed for this breakthrough, but it was put on hold with the advent of World War II. The Tour was discontinued in 1943, and that year Hogan was inducted into the U.S. Army and then assigned to the Air Corps.

Like most celebrated athletes serving military duty, Hogan did not see combat. He trained pilots for a time but, for most of his hitch, played exhibitions to raise money for the war effort, played casual golf with high-ranking officers, practiced on his own, and entered the occasional Tour event when the circuit began again in 1944. Still, he was away from steady, high-level competitive golf for 3-1/2 years.

When Hogan returned full-time to the tournament circuit, he made up for lost time with characteristic tenacity. In his first outing after his discharge, in the fall of 1945, Hogan won the Portland Invitational with a record-setting 72-hole score of 261 -- 27-under-par.

From 1946 through early 1949, playing what he would later describe as the best golf of his life, he won 32 tournaments, including his first and second majors -- the 1946 PGA Championship and 1948 U.S. Open.

Then, after playing four events on the 1949 winter circuit and winning twice, Hogan along with his wife, Valerie, nearly lost their lives. On a foggy two-lane highway outside Van Horn, Texas, a Greyhound bus traveling in the opposite direction moved out to pass a slow-moving truck and collided head-on with Hogan's car.

When Hogan saw the accident coming, he instinctively stretched across the front seat to protect his wife. He saved her from serious injury, and saved his life, for at impact the steering column of his car was rammed into the driver's seat.

Nevertheless, Hogan's left collarbone was fractured, his left ankle was snapped, and many of his internal organs were severely damaged. His face was smashed into the dashboard, which caused the vision in his left eye to gradually diminish.

Hogan would intimate, after he retired, that he had essentially played the last three or four years of his competitive golf career with sight in only one eye.

Furthermore, during his recuperation time, Hogan's life was again seriously threatened by a blood clot. A deft operation saved him, but his legs were left in a permanent state of weakness and disrepair.

That he survived at all was a wonder. That he would, within a year, return to competitive golf was beyond anyone's farthest consideration. But it happened, and in a most dramatic fashion. In January 1950, Hogan entered his first competition following the accident, the Los Angeles Open, and nearly won it; he lost to Sam Snead in a playoff.

The most astounding moment came in June 1950. In the U.S. Open, which at the time concluded with a 36-hole final day, Hogan barely held on to tie George Fazio and Lloyd Mangrum with a par on the last hole. In the 18-hole playoff the next day, Hogan won the title.

Had he never played competitive golf again, Hogan's extraordinary comeback in 1950 would have been enough to secure his place forever in golf annals. But he would expand on it, and mightily.

Cutting back his playing schedule to preserve his strength, Hogan entered an average of only six tournaments a year from 1951-53, most of them the majors except for the PGA, which was then a physically grueling match-play event requiring as much as two full rounds a day.

Nonetheless, during that period Hogan won eight times, five of them majors -- two more U.S. Opens, two Masters, and one British Open in his only attempt for that crown. In 1953 alone, he won what might be called golf's Triple Crown -- the U.S. and British Opens and the Masters.

He would also play on the U.S. Ryder Cup team, captain the team for a third time, produce an especially influential instructional book -- The Modern Fundamentals of Golf -- and found a golf equipment manufacturing company in his own name.

Hogan won his last tournament in 1959, the Colonial Invitational. In 1960, at age 48 and essentially retired from competitive golf, he had enough left to be in a position through 71 holes to win his fifth U.S. Open. That he lost did nothing to tarnish a reputation for golf skill and a will to excel that will live through the ages.

Advertisement