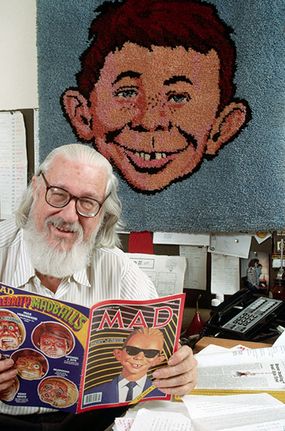

For seven decades, Mad magazine has gleefully warped generations of adolescent minds with a simple message (according to former Mad editor John Ficarra): "Everyone is lying to you, including magazines. Think for yourself."

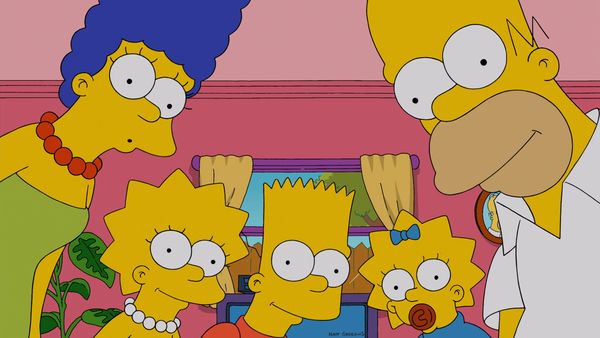

Mad magazine didn't invent parody, satire, irony and "snark," but Mad's subversive comic sensibility set the tone for everything funny that came after it, from "Saturday Night Live" to "The Simpsons" to "South Park" to "The Daily Show."

Advertisement

At its peak in the mid-1970s, Mad boasted a circulation of more than 2 million, at least half of them stashed under the mattresses of 11-year-old boys and passed around at recess hidden inside geometry textbooks.

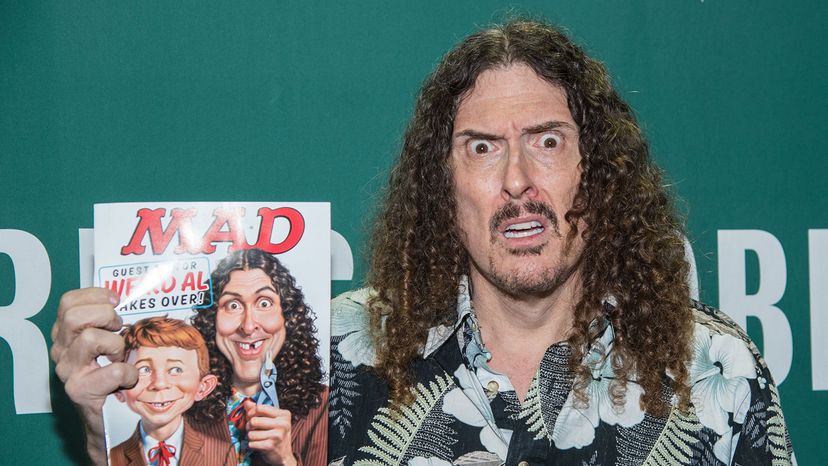

But by 2017, its circulation was just 170,000, causing the magazine to effectively shut down in 2019 and stop producing original material. But the Mad brand lives on with new releases of "best of" compilations like "MAD Mocks Music," a special 70th anniversary issue at Barnes & Noble and, more importantly, through its indelible influence on American comedy.

Advertisement