Come spring, the elephants of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus will hang up their spangles for good.

Feld Entertainment, Ringling Bros.' parent company, announced on Jan. 11 that it will retire the show's 11 Asian elephants in May 2016, considerably earlier than planned. The elephants will join 29 others, some of them family members, currently living at the Ringling Bros. Center for Elephant Conservation in central Florida. Two more Ringling elephants are on loan to zoos.

Advertisement

According to National Geographic, the company owns the largest herd of Asian elephants on the continent.

Feld Entertainment first announced the phase-out of elephant performances last March, estimating full retirement of the pachyderms by 2018. According to Stephen Payne, Feld Entertainment's vice president of corporate communications, the logistics of relocating the animals proved less complex than originally believed.

"Our staff worked through all the details needed to accommodate the eleven elephants on the circuses and determined the infrastructure and expertise were indeed there to make this happen sooner," Payne writes in an email, adding that they made the announcement now "to give circus fans and families an opportunity to see the elephants in the show again before we make the change."

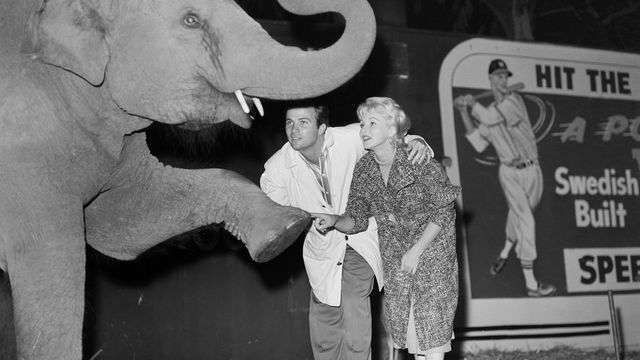

The circus has featured elephants since 1882, when legendary showman P.T. Barnum purchased Jumbo, an African elephant, from the London Zoo. Ringling Bros. merged with Barnum's circus in 1919.

The decision to end the historic act follows decades of battling animal-rights organizations. Groups like the Humane Society and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) allege that elephants, and other wild animals, face systemic abuse and cruel living conditions as performers with the circus. PETA alone has filed at least 130 complaints with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in the last 20 years, according to PETA counsel Rachel Mathews.

"PETA has decades' worth of public records, inspection reports, expert opinions, court documents, undercover footage, and whistleblower reports documenting Ringling's cruel treatment of animals," Mathews writes in an email.

Ringling Bros. staunchly denies the charges.

"They have no knowledge of our animal care, and their claims are an insult to the dedicated men and women who spend their lives caring for our elephants and other animals," Payne says. He notes that in 2014, several animal-rights groups paid a combined $25 million "to settle the fraud they attempted," referring to the outcome of an epic animal-abuse lawsuit that didn't go the way the activists planned.

Payne also notes that Ringling Bros. has never been found in violation of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA).

In 2011, the company did pay an unprecedented $270,000 in USDA fines to settle a lawsuit alleging AWA violations. As part of the settlement, Feld Entertainment admitted no wrongdoing, reports CNN.

The company acknowledged in March that public sentiment has turned against the use of elephants as performers, but Payne says retiring the animals was ultimately a cost-benefit analysis. Navigating the myriad local ordinances governing elephant performances throughout the country became unmanageable, he says, explaining, "You cannot route a tour that way."

Some jurisdictions have banned wild-animal acts entirely. Others have banned the use of "bullhooks," or guides — long rods topped with pointy metal hooks that are standard elephant-handling equipment.

Guides give elephants tactile cues as to what the handler wants, and according to the American Veterinary Medical Association, they are humane tools when used properly, to apply gentle pressure on the skin.

According to Mathews, Ringling Bros. uses them to beat, poke and jab.

To Payne, this is just the type of assertion that led to the demise of a beloved act.

"Basically," Payne writes, "enough lies about our animal care were told we concluded that instead of fighting a patchwork quilt of regulations we could use those resources for even more elephant conservation."

For the 11 elephants on tour, this means trading 1,000 shows a year and hours in cramped train cars and trucks for what Payne describes as the easy life — herd mates, pastures, toys and contributing to cancer research.

(Elephants get cancer at much lower rates than humans. The Ringling center's inhabitants help pediatric-cancer researchers study the phenomenon.)

Mathews has a different take on life at the center, claiming it's "nothing more than a breeding compound, where conditions for animals are nearly as bad as they are on the road."

For PETA and Ringling, a meeting of the minds is likely not in the cards. As for circus audiences, though, Payne says they needn't worry.

"Remember that this is just about the elephants — we are still going to feature a lot of other amazing animals," he says, including tigers, lions, horses, camels and dogs.

Mathews says PETA will fight until every one of them is retired, too.

The "Greatest Show on Earth" goes on hiatus in May, returning in July about 40 tons lighter.

Advertisement