We tend to take it for granted, the role of artists' perception in art. Surrealism, Abstractionism, Modernism -- none of them rest on visual reality, but instead on the artist's treatment of visual reality, the distortion or abstraction inherent in perspective and intent.

But it wasn't always this way. There was a time when most fine art strove for realism. Great portraits were true representations of the human subject. Landscapes looked a lot like the natural world.

Advertisement

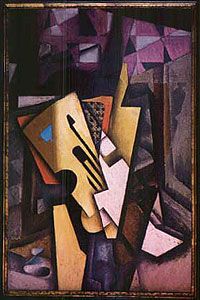

While it's nearly impossible to pinpoint the beginnings and ends of art movements, Cubism represents a clear-cut, intentional break with art as visual realism. Rather than accuracy in viewpoint, Cubists strove to display its malleability. For the first time, a single image could simultaneously embody multiple vantage points.

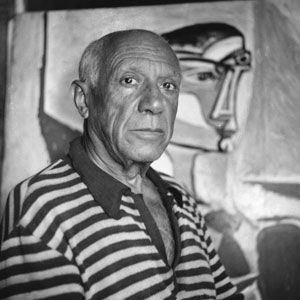

From roughly 1907 to 1914, artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Fernand Legér, Juan Gris and Diego Rivera broke down the visual world into geometric shapes, analyzed it from various angles and reassembled it how they saw fit. While earlier art strove for depth, Cubist paintings draw attention to the two-dimensionality of a canvas.

The abstractionism in Cubism, and its reliance on the internal will of the artist over external visual reality, paved the way for later art movements like Dadaism (late 1910s to the early 1920s), Surrealism (early 1920s) and Pop Art (1950s). Cubism's roots can be traced to early 1900s Paris, where two painters were producing what would turn out to be a new form of art. There they created what is arguably the most influential art movement of the 20th century.

It began in 1907 with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Advertisement