Salvador Dalí's paintings are among the most easily recognizable in the world. Oozing pocket watches, bleak expansive landscapes, erotic and grotesque nudes, melting body parts supported by precariously placed crutches, spindly legged elephants that seem certain to topple -- all are among the many classic components that so often frequent Dalí's hallucinatory dreamscapes and serve to distinguish him as both a preeminent painter and a complete weirdo.

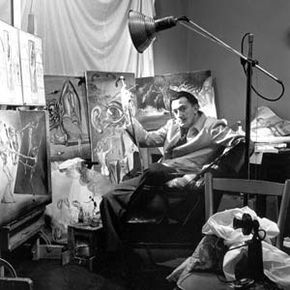

Dalí, who lived from 1904 to 1989, was a member of the Surrealist movement. And like many of the Surrealists, he dabbled in other artistic genres apart from painting and writing. For example, Dalí co-wrote two short films ("Un Chien Andalou" and "L'Age d'Or"), and he was also the madman behind the dream sequence in Hitchcock's movie "Spellbound." Dalí designed jewelry, magazine covers, costumes, advertisements and furniture. He created sculptures, lithographs, installation art -- and in everything, he was, above all, experimental.

Advertisement

Pinning down Dalí is an exercise in futility; the man was larger than life and many different things to many different people. His often off-the-wall behavior, strange artistic outpourings and shockingly outlandish claims have at different times been called scandalous, brilliant, bizarre, riveting, appalling, inspired, grotesque, superb, subversive, egotistical, imaginative, disgusting, energetic and flamboyant -- you get the idea. While simultaneously esteemed and despised, there's no question that Dalí completely captured people's attention.

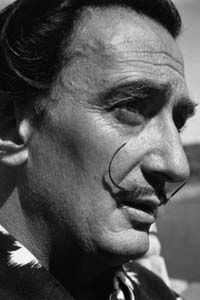

And that was no accident. Even apart from the attention his artwork received, Dalí adored fanfare (sensational or controversial, it didn't matter) and was known for shameless self-aggrandizement and self-promotion. Then there was the classic Dalí look: full-length fur coats, canes and that mesmerizingly maniacal mustache. The look was completed by Babou, his pet ocelot.

Details concerning Dalí's life are murky, with much of the confusion coming from the artist himself. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than when it comes to the details of Dalí's childhood and some of his stranger psychological claims, which we'll explore on the next page.

Advertisement