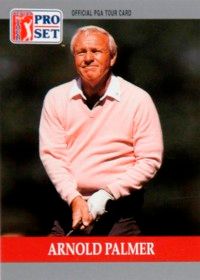

Arnold Palmer epitomized that rare athlete who achieves a level of popularity that transcends his sport to becomes a national folk hero.

His rise to such heights was the result of a unique combination of elements. When Palmer won the 1960 U.S. Open, with an exhilarating final-round 65, the national network telecasting of golf was just beginning to take hold.

Advertisement

The conclusion of his great round was seen by millions, who also saw in the author of that remarkable finish a refreshingly animated athlete responding with an obvious, visor-tossing exhilaration that golf fans had not seen before.

What's more, the way Palmer played the game had an endearing quality with which the mass of average golfers could identify.

He swung hard and fast and had a less than classic, gyrating follow-through. He hit the ball with great authority and for distance, and he did not play with the stolid caution of golfers past.

Palmer took chances, "went for broke," and the crowd loved him for it. They created what came to be called "Arnie's Army," loyal followers who chased after and cheered him through his prime and even after he was well past his most effective years as a competitive golfer.

Had Palmer not also been a winner, all his charismatic charm would have been little more than an interesting sidebar to golf. But he was a winner, a big winner. By 1960, Palmer had already won 13 tournaments on the PGA Tour, including the first of the four Masters he would capture.

The 1960 Open victory at Cherry Hills C.C. in Denver had the stuff of which legends are made. The final round was played on Saturday afternoon. During lunch, Palmer asked companions, "I may shoot 65. What would that do?"

"Nothing," said golf writer Bob Drum. "You're too far back."

"The hell I am," Palmer snapped. "A 65 would give me 280, and 280 wins Opens." Three times Palmer had tried to drive the 1st green, and three times he had failed.

That afternoon, Palmer went for it again. He hit a smoking tee shot, his ball bounded through a belt of rough fronting the green, and it rolled onto the putting surface 20 feet from the hole. It was a 346-yard clout. He birdied that hole, and five more on the front side, to turn in 30, and a hero was born for the ages.

Earlier in that same monumental season, Palmer had won his second Masters. When he entered the British Open, the world of golf was excited by the possibility of the first modern-day Grand Slam -- victories in the four major championships (the PGA would be the fourth leg).

Palmer came up one shot shy of the winner at St. Andrews, Kel Nagle, but in merely going to the British Open he revived interest in the grand, old event, an interest that had flagged in previous years because the dominant American stars regularly bypassed it.

With the game's history in mind, Palmer conscientiously sought to bring the British Open back to its rightful place in golf. He did that, by dint of his play and his personal appeal, and the game should be eternally grateful to Palmer for this one of his many contributions to it.

Arnold Daniel Palmer was born in 1929 in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. His father, known as "Deke," was the greenkeeper at Latrobe C.C. and later became its head professional.

A good golfer himself -- although lame in one leg from having polio as a youth -- the elder Palmer was a hard-driving man who demanded the best from his only son, whom he taught to play when Arnold was three years old. The lesson was simple: Eschew "classic" form if it didn't come naturally. Take the club back slowly and then hit the ball as hard as you can.

There were times in his career when Palmer considered altering his swing to make it more fluid and graceful, but he would inevitably go back to his roots and rock and sock it even when it seemed to cost him victories.

For example, Palmer's bold style of play was counted as the reason he lost the 1966 U.S. Open, at the Olympic Club in San Francisco. Palmer had a seven-shot lead over Billy Casper with only nine holes to play.

Rather than play carefully and nurse his huge lead, he continued to fire away, because that was his way and also because his mind was on breaking the U.S. Open record score of 276. He needed to par the last six holes to do that, but he instead went 6-over to finish in a tie with Casper.

He lost in the playoff, again after building up a substantial lead early but giving it up with his slash-and-burn style of golf. But Palmer's golf swing and how he used it reflected his true daredevil character, which is why he was so admired by golf fans, win or lose.

Palmer played some amateur golf prior to turning pro, and he showed promise. He entered Wake Forest University on a golf scholarship arranged by his best friend, Buddy Worsham, younger brother of the 1947 U.S. Open champion.

Arnie won the Southern Intercollegiate title in 1950, twice went to the semifinals of the prestigious North and South Amateur, and won the celebrated All-American Amateur at Chicago's Tam O'Shanter C.C. by nine shots over the formidable Frank Stranahan.

But Palmer's ascent in golf was slowed by the tragic death of his friend Worsham, who was killed in a car accident. Palmer dropped out of school, joined the Coast Guard, and when discharged took a job as a paint salesman. He did keep up his golf, though, and -- once past the pain of Worsham's death -- got back in gear.

In 1954, Palmer won the U.S. Amateur championship at the Country Club of Detroit. He would always say that this was the toughest victory of his career, owing to the match-play format.

Later that year, Palmer turned professional with the intention of playing the tournament circuit. He never did hold a club job, but he did come to own the golf club where he grew up as well as the Bay Hill Golf Club in Orlando, where he annually hosts the PGA Tour's Nestle Invitational. Palmer left the game fourth in the PGA Tour's record book with 62 wins.

His four Masters came every other year from 1958-64, and all were won in grand fashion. In 1958, Palmer eagled the 67th hole to give him the edge he needed. In 1960, he birdied the last two holes to edge Ken Venturi by a stroke. In 1962, he fired a sizzling 31 on the back nine of a playoff to win by three. And in 1964, he romped to a six-shot victory.

Palmer's most productive stretch of winning golf came from 1960-63, when he won 29 tournaments. He also won 19 international events, including two British Opens (1961 and 1962), and 10 Senior PGA Tour tournaments, including the U.S. Senior Open (1981).

He is tied with Jack Nicklaus for the most consecutive years winning at least one tournament (17), and he was the first golfer to reach the $1 million mark in career prize money.

Palmer also holds the record for most Ryder Cup Match victories with 22. He played on six U.S. Ryder Cup teams and was twice the captain. When Palmer began play on the Senior Tour in 1980, he won his debut tournament, then took nine more senior PGA wins in the next nine years, including three in 1984.

Diagnosed with prostate cancer in January of 1997, he was playing in a tournament less than two months later, and played in his 43rd Masters a month after that. He was presented with the PGA Tour Lifetime Achievement Award in 1998. He officially retired from tournament play on October 13, 2006.

Moreover, with his trim waist, muscular arms and upper body, and power-game style, Palmer changed the perception non-golfers somehow had of the game -- that it was not athletic.

That, along with his ready smile, an unpretentious manner that projected easy access by the gallery (he became known for never passing up an autograph request), and a readiness to talk openly with the press whenever asked, would make Arnold Palmer a household name -- golf households and otherwise.

Advertisement