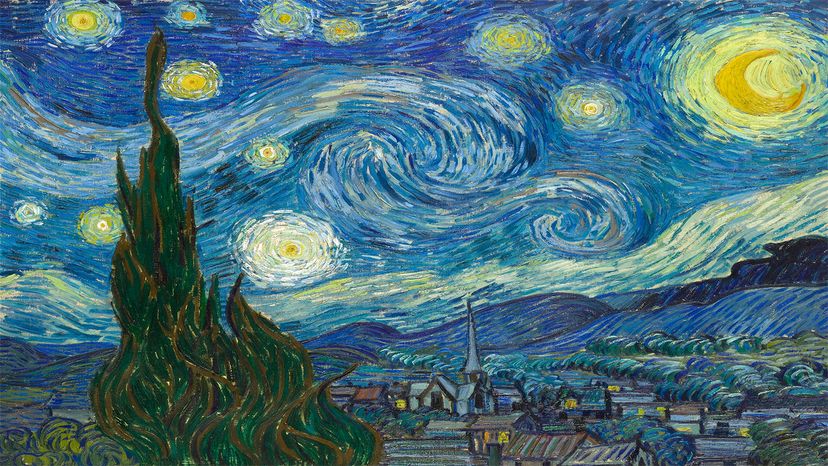

Post-impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh is known for his use of bold color, especially yellow. In one of his most famous works, "The Starry Night," (1889) a bright yellow moon breaks through the swirling night sky where it is joined by many stars. To achieve the special lunar hue, Van Gogh chose a popular pigment just years before it was deemed illegal and pulled from the market.

This special hue, Indian yellow, had also appeared in the works of several other well-known artists, thanks to its striking appearance and rich luminosity. But it was tinged with ethical issues that ultimately led to its downfall.

Advertisement

"I recall early on being very taken with the richness of that pigment and therefore paint," states Frank Piatek, professor of painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in an email. "But I was very disheartened when I had reason to look up the pigment in Ralph Mayer's compendium on artist's materials. In that text he cautioned against using that pigment as it may be prone to fading in sunlight, but also because of its curious form of manufacture."

And it was precisely that manufacturing process that shifted the status of the previously appreciated color.

Advertisement