Mention pro wrestling in public and you're likely to get a livelier debate than you would with politics or philosophy. Is it a sport or a show? Is it real or fake? Who was the greatest wrestler ever? Where is "Parts Unknown"?

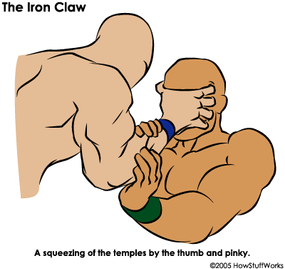

By the time you're done reading this article, you'll have enough pro wrestling knowledge to put anyone who disagrees with you into a Sleeper Hold, unable to budge the Iron Claw of your logic.

Advertisement

You'll learn how wrestling got started and how wrestlers accomplish seemingly superhuman feats without killing themselves and each other. You'll also learn about the top stars of the past and present. And if you're already an expert on all things in the squared circle, you'll discover that the action behind the scenes is often more bizarre and convoluted than what goes on in the ring.

The Basics

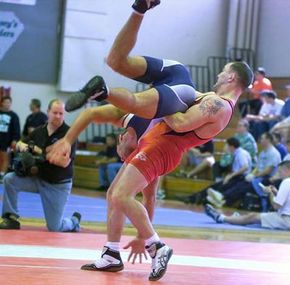

The basic idea of wrestling -- two people competing in a physical combat -- is ancient. The Greeks engaged in a form of wrestling that has survived today as freestyle wrestling. The Roman Empire adopted elements of Greek wrestling with an emphasis on brute strength. The resulting form, known as Greco-Roman wrestling, requires wrestlers to perform all moves on the upper body only. Freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling are the two international amateur forms practiced today in the Olympic Games. They have clear rules and weight classes. Points determine winners, and violations result in disqualifications. You can find more information on the rules of amateur wrestling here.

How is professional wrestling different? Unlike amateurs, professional wrestlers are paid. They also tend to be more skilled. A sporting commission regulates amateur wrestling, but pro wrestling is intentionally unregulated. In its early days, wrestling fell under the state sporting commission authority. League owners soon realized that they could avoid the hassle by classifying their shows as entertainment, not a competitive sport.

Wrestling does have rules, which we'll explain in more detail later. However, the rules are loosely defined and loosely enforced. The skills of the wrestlers do not determine the outcome of the match. Instead, writers work on plots and storylines well in advance, and every match is another chapter in the story. Who wins and who loses is all in the script.

Does that mean that wrestling is fake? It's true that the plots are predetermined and the moves are choreographed. Wrestlers aren't really trying to beat up and injure each other. Sometimes, the bitterest enemies in the ring are really best friends, and the outlandish stories surrounding the characters are usually not true. However, simply calling wrestling "fake" is like calling an action movie fake. When you see a movie, you know that the actor didn't really jump a burning car over an exploding bridge, but you're still entertained. Stunt people and special effects crews worked to make those scenes seem real, and their work can be very impressive.

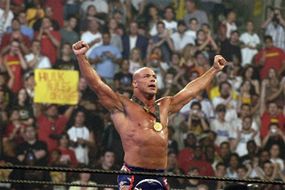

Pro wrestling is like that. Most wrestlers are exceptional athletes who train for many hours each day to maintain their physical condition. They practice for years to learn both the moves and how to execute them safely while still making it look dangerous. They suffer many injuries, sometimes severe. Their schedules are grueling. There's certainly nothing fake about flying 20 feet through the air from the top rope.

Next, we'll learn about kayfabe and the meaning behind some wrestling terminology.

Advertisement