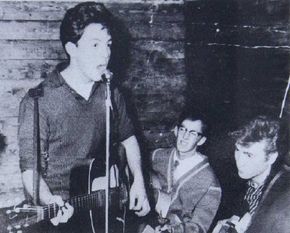

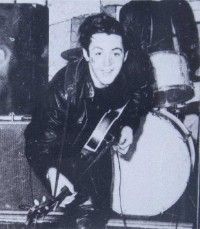

As his emotional life was in turmoil following his mother's death, one of the few things that teenage John Lennon had left to cling to was his music.

It was becoming increasingly apparent that he was simply wasting his own and everyone else's time at art college, and that he had neither the qualifications nor the application to hold down a job that would provide him with financial security. Making music was what he enjoyed most, and it was now beginning to dawn on him that this would probably be his only route to some sort of success.

Paul McCartney, for his part, also appeared to be taken in by this idea. An academically bright boy who had, until now, always excelled at school, he too began "sagging off" (cutting class). This was not only in order to make lunchtime rehearsal sessions at the art college, but also so that he and John could go back to the McCartney home in Allerton. There, during the afternoons while Paul's father was out, the pair indulged in their favorite pastimes: songwriting and discussing girls.

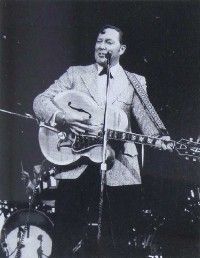

Musically, Paul was easily the more accomplished of the two, capable of playing more instruments and writing songs of his own. John, on the other hand, was the original. Whereas other British performers at the time -- including Paul -- tended to imitate many of the characteristics of their favorite American artists, often singing with a pseudo-American accent, John's approach was all his.

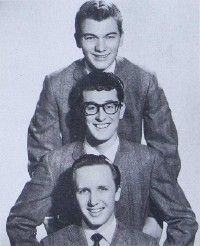

His strong, raw voice was made for rock 'n' roll, and while he utilized some of the vocal mannerisms of Buddy Holly, his pronunciation was clearly English. He wasn't interested in sounding like other people, but just in being himself. The way in which he ripped his way through songs was true to his character: no frills, no nonsense.

Although John had the greater talent for lyrics and Paul had a broader musical range, there were no strict ground rules in their collaboration. During the first years of their partnership, they would often work together when writing words and tunes, and although in some cases one or the other person had contributed far more to a particular song, they agreed early on to always share the credit.

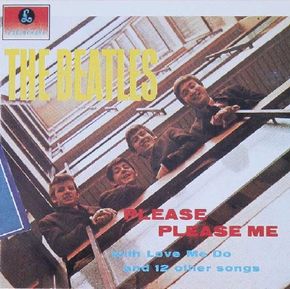

Although by 1964 they were rarely composing side by side, "Lennon-McCartney" continued to appear under each title until the Beatles split in 1969. Regardless, the identity of the person singing the lead vocal provided an easy clue as to who originated each song.

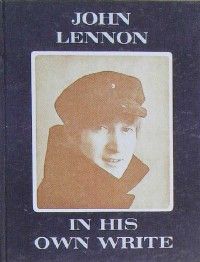

Among John's first compositions were "Winston's Walk," which was never recorded; "Hello Little Girl," which was later recorded by the Fourmost; and "The One After 909," which was recorded by the Beatles in 1963 (unreleased) and 1969 (released on the Let It Be album). His lyrics at first tended to be of the "blue moon in June" variety -- simple love poems that rhymed neatly. But as his confidence grew and he began to experiment more, the word structures became more intricate and the subject matter less familiar.

Soon a noticeable difference of style emerged between the two young composers: Whereas Paul tended to construct little stories, John concentrated on writing in the first person and expressing his own emotions. It was John who was experiencing the joys or pains of love, and who would use his songwriting to relate, much later on, his political views, his experiments with drugs, and numerous other incidents that took place in his life. And while Paul's songs were usually upbeat and optimistic, John's could often be probing and cynical.

"I was always like that, you know," he asserted during his 1980 interview with Playboy's David Sheff. "I was like that before the Beatles and after the Beatles. I always asked why people did things and why society was like it was. I didn't just accept it for what it was apparently doing. I always looked below the surface."

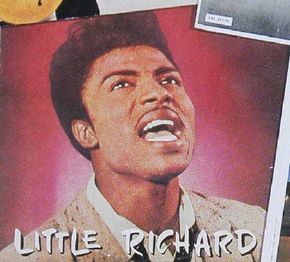

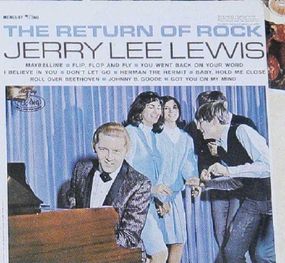

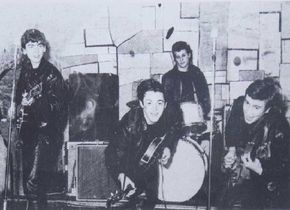

Whereas in America during the 1950s artists such as Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Sam Cooke, and Buddy Holly wrote a lot of the material that they performed, the situation was not the same in Britain. There, the stars of the day usually recorded either songs that had been penned by specialist composers, or "cover" versions of American hits.

It was, therefore, highly unusual for two English schoolboys to be compiling their own catalogue of songs which they, themselves, could perform. Furthermore, they didn't produce simple carbon copies of the sounds that they heard from across the Atlantic. Instead, they assimilated various American melodic styles and rhythms and put their own beat-oriented slant on them.

To the by-now 16-year-old Paul McCartney, John was someone to secretly admire; a hard-rocking Teddy boy, two years his elder, and a potentially dangerous influence who (as Paul's father had warned him) could get him "into trouble." Naturally, Paul was eager to hang out with a guy like this!

To John, on the other hand, Paul was a baby-faced, wide-eyed smoothie, who was gracious and hard working. On the surface, not his type at all, but John was nothing if not sharp. He immediately recognized that Paul's qualities could be extremely beneficial, both to him and to his group. Paul's musical talent would be of great value, his will to succeed would inspire John to write and the band to improve, and his pretty looks would charm the girls.

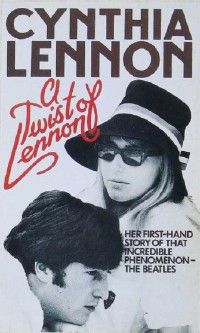

So, as he had done before, John had teamed up with someone who was not much like him, but who complemented him perfectly. Well aware of what he needed and what he himself had to offer, he formed his closest relationships with people who could both play on his strengths and make up for his weaknesses. This was the case with Paul; his girlfriend Cynthia Powell; and, just as remarkably, Stuart Sutcliffe, a small, shy, Scottish-born artist whose incredible talent had taken the college by storm.

Sutcliffe's introvert personality, vulnerable on the surface but extremely strong underneath, contrasted greatly with the extrovert John, who was always able to attract a crowd around him, and whose hard outer appearance concealed a soft center. Both had very sharp minds, however, and they saw qualities in each other that they respected and desired.

John's mean and moody appearance was largely a pose, used for specific effect, but with Stuart it was natural. He didn't need to do much to attract the girls; his looks saw to that, as did an artistic ability which had the college instructors predicting future greatness. The fact that he led a bohemian lifestyle -- living in a run-down room with a shared toilet in a large Georgian house -- only added to the air of mystique around him, and to John's fascination.

This was the heyday of the "beat generation," of unorthodox young poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, and of the beatniks who read their works and spent long hours analyzing them. Unlike the traditional rhymes, these writings dealt with stream-of-consciousness, whereby the poets put the various unrelated thoughts that came tumbling out of their heads straight onto paper in verse form.

John, whose own love for wordplay was as strong as ever, was absorbed by all this. He and Stuart, together with college friends Bill Harry and Rod Murray, would stay up late into the night, drinking and talking about the new poetry.

Inspired by these sessions, as well as the thought of spending more time with Cynthia and less with his strict Aunt Mimi Smith, John duly informed his aunt that he was moving out of her house and into Stuart's place in Gambier Terrace, situated conveniently around the corner from the college.

In a later interview with author George Tremlett, Mimi recalled John telling her, "I feel like a baby living at home." before tactfully adding. "Anyhow, I can't stand your food!" This was all that Mimi needed to hear. She let John pack his bags and gave him his full college grant money. For now, the Teddy boy would become a beatnik.

Within four weeks, however, all the money that was supposed to last him three months had been spent, and the flat that he was sharing with Stu and Rod Murray was in complete chaos, with clothes, paints, and garbage spread all over the floor around the mattresses that were being used in lieu of beds. By the middle of winter it was so cold, and they were all so broke, that, so the legend goes, they were reduced to burning in the middle of the room what furniture they had in order to keep warm.

Having left Mimi's in a mood of supreme confidence, boasting that he would be surviving quite happily on a diet of Chinese takeout food -- "bamboo shoots and things" -- John suddenly reappeared at her house with his tail firmly between his legs. Too proud to admit, however, that things hadn't gone exactly to plan, he tried to give the impression that this was just a friendly visit, and asked casually "Don't I get a cup of tea, then?"

Mimi went along with his little act, and quietly continued cooking the dinner that she was preparing for herself. This was just too much! Not having eaten for days, John couldn't resist the smell of steak and mushrooms that was wafting above his head, and so he suddenly burst into the kitchen and shouted at her: "I'll have you know, woman, I'm starving!"

Mimi gave him dinner and allowed him to stay the night. The next morning, with extra money from her in his pocket, John set off once again for the mayhem of Gambier Terrace and further adventure.