Spoiler Alert: This article includes details about the real events that inspired the 2006 film "We Are Marshall." These events are central to the film's plot and ending.

The story told in "We Are Marshall" sounds a little like the invention of a screenwriter. An airplane carrying a university football team crashes, killing nearly all of the players, most of the coaching staff and several prominent fans. The university and the close-knit surrounding community are devastated but decide to persevere. A new head coach assembles a team of freshmen and athletes who have never played football. This motley crew goes on to win its first home game with a record-breaking number of fans in attendance.

Advertisement

But in spite of sounding like they were made for Hollywood, these events really took place. On Nov. 14, 1970, Southern Airways Flight 932 crashed on approach to Tri-State Airport in Kenova, West Virginia. Marshall University had chartered the plane to carry its football team, the Thundering Herd, home from a game against East Carolina University. All 70 passengers and five crew members were killed. Only a handful of the Thundering Herd were not on board.

The plane, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-31, had flown from Atlanta, Georgia, to Kinston, North Carolina, to pick up its passengers. Flight 932 then left Kinston at 6:38 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST), and the flight, expected to take 52 minutes, progressed normally. But about 1 mile (1.6 meters) from the Tri-State Airport runway, the airplane struck trees on a hill, cutting a 75-foot wide, 279-foot long (22.8 x 85 meter) swath through them before crashing into the ground. The plane exploded on impact. The main wreckage landed only 4,219 feet (1,286 meters) from the runway.

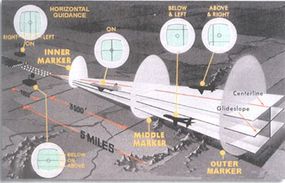

The tower controller started watching for Flight 932 after it passed the Instrument Landing System's (ILS) outer marker. At 7:36 p.m. EST, the staff noticed a red glow to the west of the runway. The controller had not made visual contact with the airplane, but he saw the explosion and fire that resulted from the crash. Unable to contact the plane, the tower crew started emergency procedures. Police and fire officials as well as the National Guard responded.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigated the crash and quickly ruled out gross negligence or foul play:

- The airplane was in good condition and had been properly maintained. It had refueled in Kinston before its departure.

- Its crew had filed an accurate flight plan and adhered to it.

- The plane was not overloaded, and its center of gravity was within normal limits.

- The pilot and first officer were experienced and qualified to make the flight.

- The pilot had a 20-hour rest period before reporting for duty. The first officer had an 18-hour rest period.

Investigators found no sign of any sort of catastrophic failure in the structure of the airplane, its instruments or its power system. They also found no serious missteps at the airport. The runway was wet due to weather, but the flight crew knew about its condition and had adjusted their descent to compensate. Although it was raining and cold, airport personnel reported a visibility of five miles (eight kilometers) until just after the crash. The runway lights and notification beacons were all functioning.

However, because of the nature of the terrain around the airport, it did not have a glide slope as part of its ILS. A glide slope transmits a signal to the aircraft to help the pilot make sure that the plane descends at the right angle. Because of the absence of the glide slope, the landing was considered a non-precision instrument approach. The airport was allowed to operate without a glide slope, but without it, pilots had one less tool for landing safely.

Investigators also ruled out the height of the trees as a factor. The trees were too tall according to the Federal Aviation Regulations in use at the time. However, these regulations were used for administrative purposes, like allocating money or notifying the public of construction. The height of the trees did not violate the U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedure (TERPS). In other words, under normal circumstances, the height of the trees should not have affected a plane's ability to land.

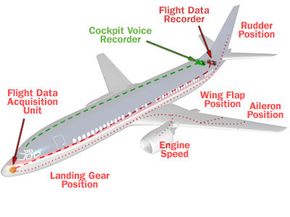

The NTSB's final analysis was that the airplane had crashed because it was below the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA). In other words, it crashed because it was too close to the ground while descending. But the NTSB was not able to determine precisely why the plane was flying too low. Investigators narrowed it down to two possibilities. According to the accident report, "the two most likely explanations are (a) improper use of cockpit instrumentation data, or (b) an altimetry system error" [source: NTSB Aircraft Accident Report]. In other words, either the instruments were functioning incorrectly or the pilot and first officer were using their data incorrectly.

We'll look at these two possibilities in more detail in the next section.