Nevada is a land of glitzy casinos, legalized prostitution and -- most notably of all -- giant, man-eating sandworms.

Sure, tourism and silver mining pay the bills, but the legendary graboid weaves its way throughout the state's history. Residents of Perfection Valley first reported the deadly, subterranean creatures back in 1889, and it was only four years later that U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt allegedly hunted the "noble Nevadan land shark" during a visit to the state.

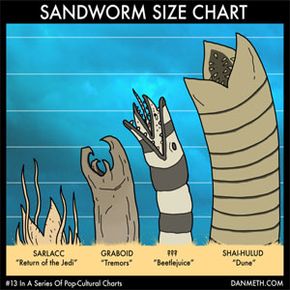

Advertisement

Later, during the late 1960s, business magnate and filmmaker Howard Hughes reportedly converted an entire floor of the Desert Inn hotel and casino into a sand-filled graboid habitat, all in hopes of harvesting consciousness-altering agents from the creatures.

While attacks on humans continue to this day, the graboid largely makes headlines these days for less lethal encounters. In 2012, the United Kingdom's Prince Harry stirred controversy when photographed nude riding an albino graboid through the streets of Las Vegas.

In recent times, graboids have appeared as far south as the deserts of Argentina, but the creature remains most notable for its presence in the Nevadan badlands.

So let's get to know these ancient and ravenous subterranean monsters. For starters, where did such a peculiar creature come from?