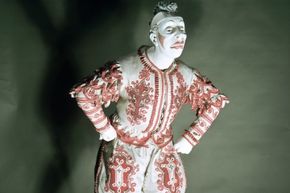

London, 1803. A young man sits before a mirror. By candlelight, he paints his face, first coating every square inch of exposed skin with white makeup. Next, he thickens his eyebrows into black arches before marking his cheeks with brilliant red triangles. Finally, he covers his mouth with a crimson grin. Wild blue hair rises like a flame from his luminous white scalp. The look is good, but not quite right. He wipes it all off and starts again.

Hour after hour, day after day, he repeats this ritual until at last a face both hilarious and demonic flickers into view, a face so outrageous that he's finally satisfied. Donning slippers, preposterously oversized pantaloons, a riotously patterned shirt and an extravagant ruff, he steps onstage. Joseph Grimaldi, star of the London stage, has invented the clown [source: Scott].

Advertisement

Grimaldi was already a lead performer in the pantomimes that were then popular in Regency England. But the figure he created in the early years of the 19th century became so legendary that clowns are still known by the nickname "Joey," the name Grimaldi gave his character. The makeup, the hair, the costume — they were all copied as performer after performer tried to recapture the magic that Grimaldi brought to the stage.

But, of course, it was more than just face paint and pantaloons that made Joey famous. His performances were renowned. Doing battle with animated vegetable-men, parodying contemporary figures, and dancing and singing with charismatic energy, Grimaldi was adored by everyone from Lord Byron to Charles Dickens. Even today, clowns often use his famous catchphrase, "Here we are!" as they bound onstage [source: Scott].

And while Grimaldi is credited as the inventor of the classic clown figure, the truth is that clowns have been around since the beginning of recorded history and seem to be present in virtually every culture in one form or another. The word "clown" itself goes back at least as far as the 16th century. Etymologists speculate that it comes from a German word meaning "country bumpkin" [source: Oxford Dictionaries].

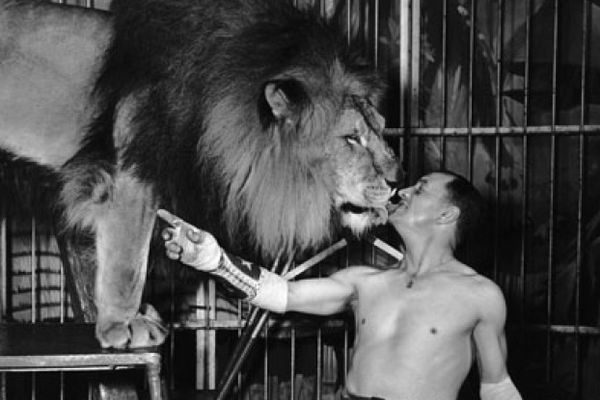

From ancient Egyptian tricksters to European jesters, from Bozo to killer clowns, the universal figure of the anarchic fool has always teetered on the tightrope between laughter and terror.

Advertisement