When Leonardo Da Vinci finished "The Mona Lisa," he had created a masterful work of art that stands on its own. Today the painting hangs in the Louvre in Paris and is known around the world.

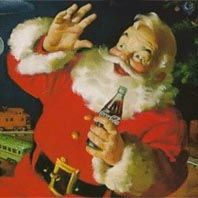

But what if Leonardo lived today? What if he had painted "the Mona Lisa" for an advertising agency as a background for a magazine ad? In that case, the Mona Lisa would be an illustration. The illustration might still be well known and influential. For example, our common conception of Santa Claus comes in large part from a set of paintings by Haddon Sundblom, used as illustrations for Coca-Cola ads between 1931 and 1964. It is quite possible that Sundblom wouldn't have made the paintings, nor that they would be as widely known, if they had not been ad illustrations.

Advertisement

As you can see, the line between fine art and illustration is often blurry, but there is a distinction. In the dictionary, one definition of illustration is, "visual matter used to clarify or decorate a text." An illustration is art, but the art is serving as part of a larger whole rather than standing on its own.

We see illustrations all around us in countless different forms and formats. For example, most children's books are illustrated. Catalogs, books and magazines often contain illustrations. Most user's manuals have illustrations, though they may be crude. The Sunday comics are illustrated cartoon panels, as are comic books. Many ads on billboards and in magazines are illustrated. One way to think of an illustration is as a drawing, photograph or painting that serves a specific purpose in some larger work.

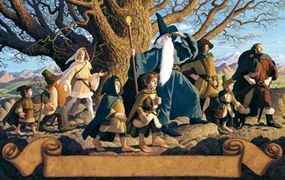

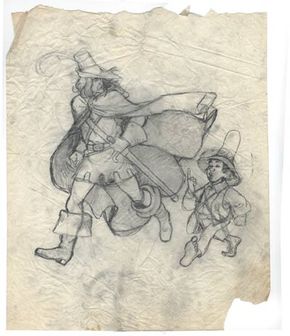

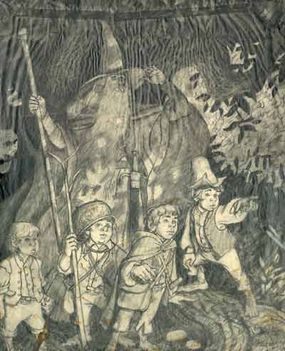

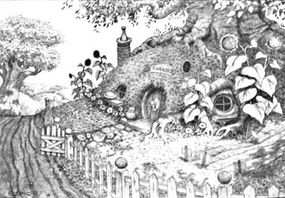

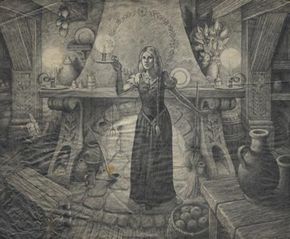

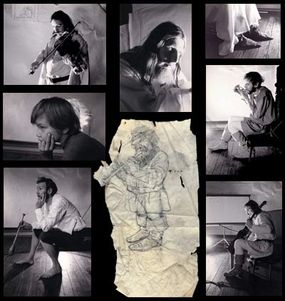

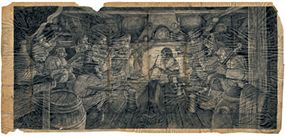

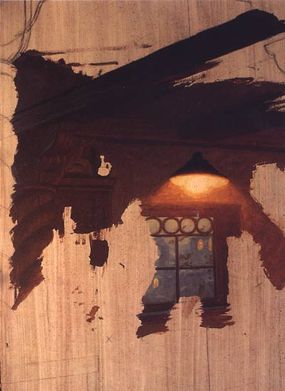

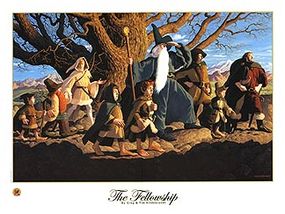

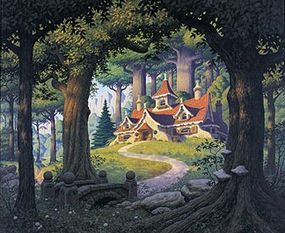

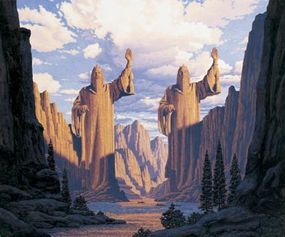

In this article, we'll look at a pair of illustrators and their very special form of illustration. Greg and Tim Hildebrandt, also know as The Brothers Hildebrandt, have been creating illustrations for several decades. They are probably best know for a set of large, elaborate paintings that they created in the 1970s to illustrate three J.R.R. Tolkien calendars published by Ballantine Books (at the time, the world's best selling calendars ever). They also created movie poster for the first "Star Wars" movie, and a wide range of other works. Their careers have spanned everything from children's book illustrations to racy pinup art. We will see how illustration works through their eyes.

Advertisement